An icon of Brutalist architecture, the Barbican has always been controversial. Voted “London’s Ugliest Building” in 2003, people were so distracted by its stony exterior they cast their verdict before knowing what was going on inside (they might have cast it earlier if they had known!). Working with a site almost completely razed by the Blitz, the Barbican’s architects, Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, seized the opportunity to propose a radical transformation of how we live; or, at least, for the middle class who could afford a flat at the Barbican.

Some say that the result is one of London’s most ambitious and unique architectural achievements: a city within a city! But this conclusion usually leaves out the Barbican’s more important legacy: being the site of one of the UK’s biggest industrial strikes. In fact, as well as being a marvel of architecture, the Barbican includes many histories of collective action by workers who have demanded more from the centre across its 60 year history. This is the only way that the most precarious workers at the institution have been able to access the rights freely handed out to other employees. Not bad for a building with so many leaks.

The Battle of the Barbican

These radical histories began when work started at the Barbican site in 1962. The site was so big that each part of the project was split into segments and each one was overseen by a different building company. The workforce that populated the site was incredibly diverse and notably full of migrants—featuring workers from Ireland, Jamaica, the West Indies, India and different countries in Eastern Europe.

By all accounts, the health and safety measures on-site were poor (even by the already scary industry standards of the 60s and 70s). Demands for better working conditions ended up costing the City of London years of building delays, though it also cost the lives of some workers as well as irreparable physical damage to others. Guess all those names couldn’t fit on a plaque as easily as Chamberlin, Powell and Bon.

In those days, minimum standards needed to be set by the workers hard and fast if they didn’t want to be taken advantage of, which is, in part, why unions and union representatives (called stewards) were so crucial to construction sites.

Let me paint you a picture of what you could expect working at the Barbican.

The Turriff site was among the first sites of action in what would be a long term struggle between workers and management. There were no toilets—just boxes full of chemicals that workers fashioned into makeshift latrines. The employers refused to build flushing toilets until at least two floors of the site had been built up and, as a consequence, workers began walking to St. Paul’s Cathedral to use their toilets en masse. It was not uncommon that the site was only ever half full, given that many workers were en route to the bathroom. It wouldn’t be long before all working rights followed them right into the toilet. In 1976, John Laing (one of the construction firms working on the site) tried to force workers who were building the arts centre to handle cladding material that had been proven to carry asbestos. Talk about needing a risk assessment! In protest of this, 500 workers walked off the site in an all-out strike lasting two weeks.

This is a story that ends with some kind of positive change—there are others that bore no resolution.

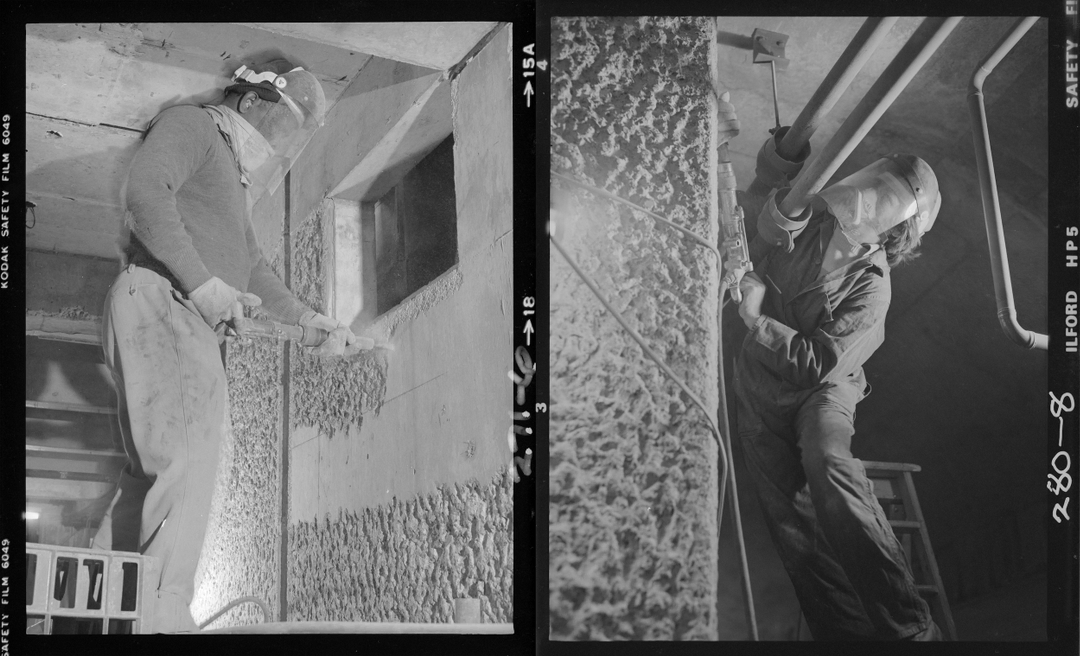

Take the Barbican’s iconic concrete texture for instance: well, you can thank a group of half a dozen workers (most of whom were Black) for doing that by hand using bush-hammers all across the Barbican site. This work was infamously horrible, extremely dirty and resulted in the majority of these workers suffering from ‘white finger’—also known as Hand-Arm Vibration Syndrome—causing long term damage to nerves in their arms, wrists, hands and fingertips. No amount of union action could ever fix that. The building looks a little more brutal once you know how it was made so beautiful.

As you can imagine, big bosses and architects were annoyed that unions might ask for bathrooms and even have an opinion on what material could be used to clad their buildings. So, in 1965, they decided that they were done with it! First, they sacked 380 workers when some of them refused to show their union cards, then they tried to hire a few hundred other workers on the condition that they sign a contract giving up their right to strike. This “deal” led to a huge collective push against the document, not just by workers at the Barbican but across London. In that same week, 2,000 workers from across London’s biggest construction sites went on strike in solidarity with the Barbican workers. Unionised workers formed pickets on various Barbican sites, and construction came to a halt. The construction company attempted to bring other workers in on a bus, but this was stopped at the picket line by striking workers who smashed the coach to bits. As a result, and under mounting union pressure, the construction firm agreed to re-employ all previously sacked workers and scrapped the proposed contract.

By 1966, the architects were extremely behind on their architectural plans and kept issuing changes to the construction site, which in turn impacted workers’ abilities to operate, and more importantly, their ability to earn bonus payments (which made up for their low wages). Workers would build a wall, only to be told days later that the architects didn’t want the wall THERE they wanted it HERE. The Barbican’s concrete structure made this even more difficult as it meant that everything was more or less permanent. For the architects, the ends justified the means; especially when they weren’t the ones that had to pick away at dried concrete for months.

Long story short, architectural delays combined with issues relating to non-standardised bonus payments (which were, in part, based on how quickly workers could finish architectural plans, though difficult to do if plans change every other day) led to a unilateral walkout by workers on all sites controlled by the construction firm Myton. Myton responded with a six week lock out, closing the site and halting work. This turned out to be somewhat of a blessing in disguise, giving Myton an opportunity to renegotiate bonus standards with the union. Another blessing, perhaps, is that the six-week lockout gave the architects time to catch up with their site plans. Of course, the construction workers were not paid during this time as the site remained fully closed. In this period, Myton agreed to rehire all but the six stewards that had been most involved in the initial walk out. Workers refused to return to the site without these six stewards. What was supposed to be an unpaid holiday for the workers became a yearlong battle between them, the construction companies and the City of London, halting the Barbican’s construction for 14 months and making it one of the longest labour disputes in British history. You probably won’t find that on the Barbican’s website.

What’s impressive is that union bosses actually tried to re-open the site, although they were outmatched by the workers’ solidarity with the stewards. Myton tried desperately to sneak people on-site in buses and with police escorts, but the workers stood their ground and scared them away. Crowds of between 700-800 workers would surround the buses and rock them backwards and forwards, and, in other instances, workers from nearby sites would throw bricks at the buses. These tactics kept the site closed for over a year.

By 1967, however, the site was still closed, with both the stewards and strike committee calling for an end to the strike as it became clear they would not win. The architects never took responsibility for the disputes, and never once communicated with the workers. You will find this to be recurring behaviour for the Barbican’s so-called “creative upper class”.

Despite the delays, the Barbican Arts Centre finally opened in 1982 in an opening attended by the Queen and Margaret Thatcher—great! Unfortunately, this is not the end of the labour struggle: it seems that the people doing all the work on site at the Barbican are always overlooked.

ENOUGH IS ENOUGH!: Cleaners Fight for Equal Pay at the Barbican

In 2013, the Independent Workers’ Union of Great Britain (IWGB) campaigned for a London Living Wage for cleaners at the Barbican, most of whom were migrants earning £6.19 per hour—what one might call poverty wages. Many workers at the Barbican, who were employed by the sub-contracted company Mitie, reported being racially abused, insulted and threatened. At this point, the City of London and all its official employees were proudly receiving a London Living Wage—though not the cleaners!

On 21 March 2013, the cleaners went on strike, followed by a protest on 27 April and an occupation of the Barbican’s foyer on 4 May, amongst other actions throughout the campaign. In 2014, the City of London finally caved and said that while they REALLY wanted to give the cleaners a living wage, it was really REALLY difficult to negotiate with Mitie. They promised that once they started a new contract with Servest, they would make sure to renegotiate their wages.

By the time 2015 rolled around, wages were still the same and Mitie continued to refuse the Barbican cleaners a living wage. The cleaners began to organise again—this time with IWGB’s sister union United Voices of the World (UVW). Cleaners working during this time reported regular racial abuse from management and were only entitled to minimum legal sick pay (which means you get nothing the first three days off and then £96.35 per week, which is maybe just enough to pay your rent, your food, your transport and any other needs you might have, including the needs of your partner, your parents or your kids! That’s about £13.76 per day which won’t get you much further than a lunch from Pret when you live in London.) The result of this was that workers were faced with the Dickensian choice of staying home and falling into poverty or going to work sick. Not much of a choice when you want to survive.

In one instance, a cleaner came to work on crutches as they could not afford to lose their wage. The Barbican team responded by calling the police—throwing the worker out of the arts centre. When UVW’s campaign started, Mitie threatened to sack any cleaner who joined the protests.

Amongst other actions, on 25 April 2015, UVW staged a protest in the centre and another on 31 October 2015. As a result of this three-year struggle, in April 2016, the London Living Wage was finally “won” for all cleaners employed by the City of London, including those at the Barbican. A full two years after this wage was not so much “won” but rather bestowed upon all other staff at the Barbican. That same year, the new cleaning company, Servest, tried to sack all the UVW members who had campaigned for the London Living Wage.

This was one of UVW’s first wins as a grassroots union, and led to many similar campaigns across the country and other institutions in London. They became one of the first groups of unionised workers to ask for full sick pay, as well as being one of the few unions to represent the rights of migrant workers. Again, this is perhaps one of the Barbican’s most unsung achievements—being a location for radical union organising!

Exhibit B: The Human Zoo

While cleaners campaigned for rights that are given to most producers, curators and directors at the Barbican, in 2014, the Barbican programmed Exhibit B. Exhibit B was a performance installation conceived by the white South African artist Brett Bailey that looked to—in a “serious and responsible manner”—showcase the atrocities and racism experienced by enslaved Black people in Europe and the UK. How? By re-staging Human Zoos of the 20th century and filling their spaces with Black actors in tableaus of racist subjugation. The Barbican felt it was an installation that highlighted the inequality and abuse that had happened, emphasising racism as a thing of the past, rather than providing opportunities to think through how this inequality might subsist at the institution exhibiting the work. Bailey instrumentalised the histories and memories of pain from Black communities to create art that was meant to “challenge” the viewer—but at whose expense?

To no one’s surprise (other than to the Barbican programmers and directors, apparently) this show triggered many visitors and workers. The result was a petition calling for the show to be cancelled (which gained a total of 22,800 signatures) organised by the Boycott The Human Zoo campaign, led by Sara Myers, a journalist and activist from Birmingham. This was followed by a protest of 200 people blocking the performance entrance on the opening night. The show was cancelled.

This was the Barbican’s response:

“We find it profoundly troubling that such methods have been used to silence artists and performers and that audiences have been denied the opportunity to see this important work.”

We hope that they feel similarly about Barbican Stories by platforming it in their own bookshop! Lest we forget they were so passionate about staging work that critiqued racism in 2014.

2020: Again? Really?

Fast forward to 2020 and we see the catastrophe of the COVID-19 pandemic intersecting with—among other things—the global uproar following the murder of George Floyd in the United States, which was followed by the performative circus of “anti-racism” responses by the Barbican and the whole arts sector in general. Most memorably, in June 2020, “A statement from Sir Nicholas Kenyon, Managing Director of the Barbican” was posted on the Barbican website which includes the following line:

“The Black Lives Matter movement has demonstrated the urgent need for us to take action in showing an active commitment to eradicating racism in all its forms.”

A tall order for an organisation built on discrimination!

In November 2020, it was announced that the Barbican Centre’s front-of-house staff, who are on precarious zero hour contracts, would not be receiving a 20% furlough top up from the City of London, which they received throughout the first wave of the pandemic. They were expected to get through a pandemic on 80% of the London Living Wage, which is not a living wage at all, especially when it doesn’t include sick pay. This does not include staff who did not work during the re-opening period (due to sickness or otherwise), who will now have to reapply for their jobs. The administrative staff and creative upper class of the Barbican continue to receive 100% of their furlough and the benefits that come with being a contracted employee.

Front-of-house staff were the people who opened the centre when the country came out of the first lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic. These are the staff that make up the majority of the Barbican’s non-white workers, many of whom are migrants. The fact that our lowest paid workers are migrants or marginalized people cannot be disentangled from the mechanics of racism, and definitely does not live up to the commitment of eradicating racism in even the most basic forms, let alone “all” of them.

In November, the GMB Union created a petition to ask that the Barbican Centre’s front-of-house staff receive a full top up. At the time of writing, this petition has been signed by 3,045 people. The Barbican’s response has been to say that nothing can be done.

Management continues to wash their hands of responsibility and tell workers that this has been a difficult time for e v e r y b o d y.

2021 and beyond

In line with the Government’s COVID-19 roadmap to re-opening the country, the doors open on 17 May 2021.

Almost all of the Barbican’s casual staff don’t show up for front-of-house shifts. They have moved out of London or found employment in places that value them more. The Barbican’s creative upper class have to become hosts and invigilators to open the centre.

Barbican Stories is published.

Barbican employees are shocked at the stories and recollections of racism in the book. They can’t believe that this is all true and so they dive into their minority workforce to find out for themselves, once and for all. Unconvinced and under mounting public pressure, the Barbican hires an external consultant (a friend of a director) to publish a public race report that concludes: whilst the Barbican could do better, there is no systemic issue.

2,000 workers across London’s cultural sector create a picket line in solidarity with Barbican workers. The demands of the protest are impossible and necessary.

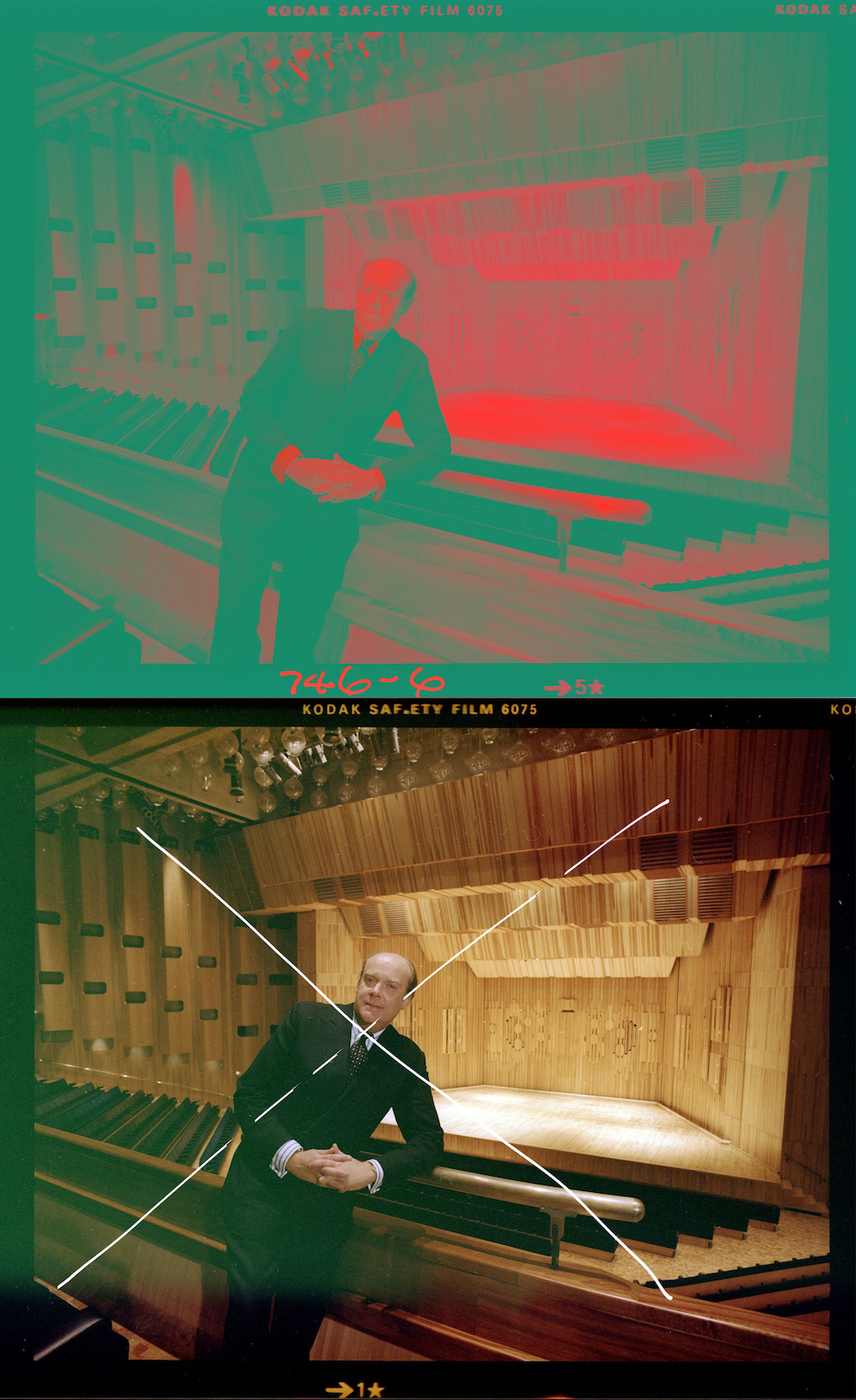

During the Barbican’s opening concert, as the conductor enters the stage to fill the auditorium with music, it is instead filled with the sound of 400 people standing up and leaving the orchestra on stage with no audience. A violinist cries.

All the employees of colour evacuate and the Barbican is left with a purely white workforce. There is a palpable sigh of collective relief: if there’s no one but white people, then we can’t be racist!

Artists stop aligning themselves with backward institutions so cultural producers at the Barbican have to become artists to fill the programme.

Whiteness clings to the walls like moisture. Visitors are too ashamed to cross the picket line.

Coffees go undrunk, B R U T A L tote bags collect cobwebs, the conservatory grows wild. The ducks leave the lake in solidarity. Old Barbican guides litter the foyer. The orange carpet turns grey with dirt.

Eventually, audiences don’t need a picket to stop them from coming to the centre. A primed and ready-to-pay cultural audience now reflects the fastest growing demographic in London. Now, these younger and more diverse audiences that make up the city’s landscape find different and better cultural spaces that actually care about them and reflect their lives without skirting around the ugly facts. Why see another token diversity event when there are now whole institutions dedicated to the complexity of the diaspora?

One by one, lights are cut from the Barbican’s many rooms and offices. They grow dusty in the absence of people. Moss grows between the cracks in the concrete.

The only room that remains open is the directorate office.

The directors maintain a throne of old catalogues, leaflets and newspaper clippings, in a never-ending meeting where the only thing on the agenda is to dust.

One unremarkable day, the Barbican ruins collapses in on itself. The debris blows away to reveal an ON SALE sign.

The only thing worth anything at the Barbican is the land it used to occupy (and even that won’t cover the debt left behind by the brutal beast).

Blitz Property Developers find EC2Y 8DS and they love a bargain.

Once again, the site is raised by the Blitz.

Histories, texts and interlocutors that have marked our thinking:

“Communist Carpenter” - Barbican Archive Mixtape: A History of the Barbican Estate by Jack Wormell (2020)

Building the Barbican 1962-1982: Taking the industry out of the dark ages by University of Westminster Researchers: Christine Wall, Linda Clarke, Charlie McGuire and Olivia Munos - Rojas (2012)

Building the Brutal - How we built the Barbican

CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF THE PRODUCTION OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT (PROBE) - University of Westminster

IWGB cleaners occupy the Barbican Centre for a Living Wage, For Worker’s Power (2013)

“Fuck off back to your own country!” - Video: IWGB cleaners occupy the Barbican Centre for a Living Wage (2013)

BARBICAN CLEANERS FIGHT FOR A LIVING WAGE AFTER CATERING STAFF VICTORY, The Multicultural Politic (2013)

The UVW Archive:

“The City of London’s artistic and cultural megaplex was mistreating its cleaners, but they fought back and the tables were swiftly turned.”

Campaigns: The Barbican Centre

Reporting on Exhibit B: Barbican criticises protesters who forced Exhibit B cancellation, Guardian, (2014), #boycottthehumanzoo

*Editor’s Note: The original version of this essay forms the introduction to the book Barbican Stories. This essay has been edited for the purposes of Decolonial Hacker.*