Fractal 1: Collaborators

At the end of March, Spanish artist Santiago Sierra’s project Union Flag, which planned to drench a union jack flag in the blood of Indigenous peoples whose lands were colonized by the British, was cancelled by art festival Dark Mofo in Lutruwita (Tasmania, Australia). In his statement on the cancellation of Union Flag, Sierra does not apologize to any offended Indigenous communities—addressed in Dark Mofo’s call for blood as an undifferentiated mass, and with whom he did not consult. He instead invokes his “good intentions” and history of a supposed decolonial art practice as justification for the validity of the work. Sierra seems genuinely confused and offended by the “vitriolic” reactions to the piece. After all, he writes,“all blood is equally red”1. Isn’t the real strength of art to be able to speak on social issues? The cancellation of this project, he implies, demonstrates a lack of faith in the potential of art to contribute to decolonial critique.

Perhaps the world is simply not ready for the controversial commentary of such principled and stalwart allies, or perhaps Sierra is a poor example. As Indigenous-Australian cultural critic Tristan Harwood writes, this is an artist who traffics in trauma. As he has done throughout his career, Sierra’s work is formed “by identifying, exploiting and repackaging the suffering of those people who have already suffered the most.” Whether by tattooing sex workers, paying undocumented people to sit under boxes, spraying Iraqis with foam, or turning German synagogues into gas chambers, it is not, as Harwood argues, the unjust structures of our capitalist societies, but the trauma of others which is in fact Sierra’s raw material.

In his own words, those who perform their suffering under Sierra’s name are his “collaborators”. Although the first definition of collaborator implies an equal and reciprocal relationship—a situation that clearly does not exist in any of his works—the second definition of the word complicates its reading: a traitor, one who works with the enemy. Is this an attempt by Sierra to disavow the power imbalance inherent in the creation of his work, or a call to implicate his subjects in their own oppression?

Sierra has always defended his work in terms of his (and the privileged gallery goer’s) complicity in its creation. “The problem is the existence of social conditions that allow me to make this work”, he says. I should not be allowed to do this, he argues, and yet I do, and isn’t that a momentous revelation on the depravity of our society? The art world seems to think so. Guilt, as Benjamin Murphy argues in a positive review of Sierra’s body of work, is the best and strongest motivator for the privileged. Acknowledging their own complicity “like a shock of cold water”, the viewer is inspired to action by works that evoke empathy and revulsion.

The conflation of performative gestures which “point to issues” or “raise awareness” in elite social spheres with artworks that enact social change is so uncontroversial it seems banal to point it out directly. The entire practice of Institutional Critique is predicated on this belief, and lauded cultural workers continue to be stalwart defenders of the power of “moral queasiness” to catalyze social change.2 Art historian Claire Bishop is not alone in her derisive dismissal of Sierra’s critics as merely concerned with “Marxist reification” or morally preaching “political correctness”3; as her much deeper assumptions of how social change operates continue to remain largely uncontested.

At the core of Sierra’s work and Bishop’s analysis is what I have referred to elsewhere as NGO-logics. NGO-logics locate the power to direct social change outside of impacted communities, and assume the largest problem in creating a more just and equal society is that relatively more powerful people are unaware or unsympathetic to the realities faced by the oppressed. The audience for such work is therefore never communities in struggle themselves (who have always recognized and practiced complex solidarities), but potential benevolent allies, only waiting to be awakened to action by the devastating emotional punch of an enlightened artist’s work.

Fractal 2: Silence

Tap. announces that Israel will neither “listen to moral preaching” nor stop its bombardment of Gaza until “complete quiet” has been achieved. So far, complete quiet has been achieved for 13 Israelis and 256 Palestinians. The International Community agrees that on this topic, silence is preferable to moral preaching.

Tap. bombs the press offices of Al Jazeera, Middle East Eye and AP in Gaza. After Israel demolishes the Gazan press offices, and after a cease fire is struck, 13 Palestinian journalists arearrested, along with Muna and Mohammed El-Kurd, whose family is facing eviction in Sheikh Jarrah. The El-Kurds, who received international media attention for their English language interviews and social media posts are charged with ‘riotous acts’ and ‘disturbing the public order’.

Tap. releases an internal reporting guide which outlines the appropriate silences in German discourse on the topic of Israel and Palestine: “we never question Israel’s right to exist as a state or allow people in our coverage to do so. We never refer to an Israeli ‘apartheid’ or ‘apartheid regime’ in Israel. We also avoid referring to ‘colonialism’ or ‘colonists.’”

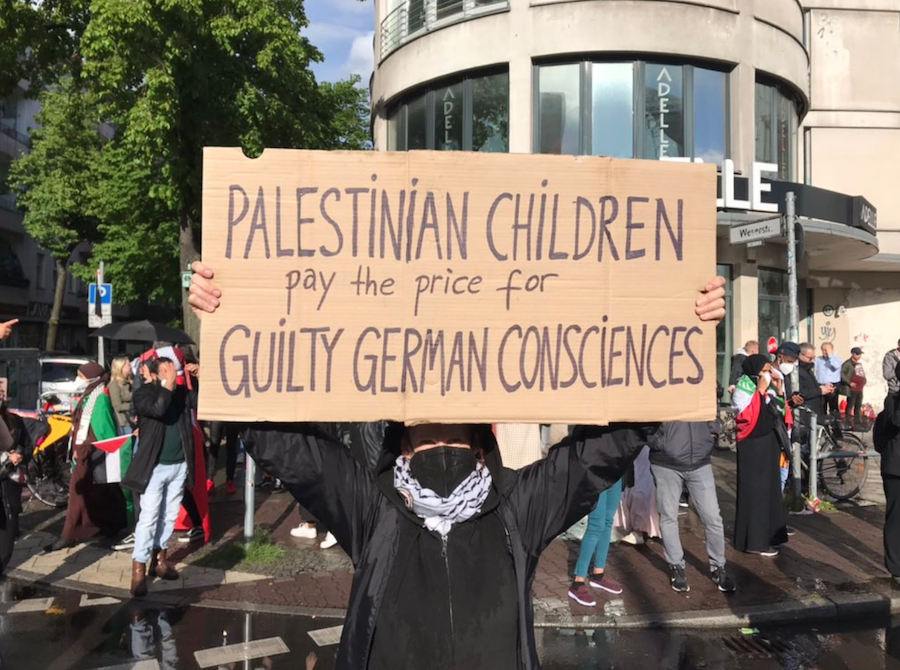

Audre Lorde wrote “your silence will not protect you…in the cause of silence, each of us draws the face of her own fear.” On the 73rd anniversary of the Nakba, I march with 15,000 others through the streets of Berlin in support of Palestine. There are many signs tying the responsibility for Gazan casualties to German guilt and settler colonialism. Together, we shout: Deutsche Waffen, deutsches Geld morden mit in aller Welt! (German weapons, German money, complicit in murder all around the world!) We point to German industries benefiting from Palestinian death. We point to international collaborators and their studied silences. Are these not also gestures? The guilty audience is inspired to action: German media erupts, charging the demonstrators with Antisemitism.

The art world tells us that it is the task of the progressive artist/informant to remove once and for all that most stubborn of intolerable German alibis – we didn’t know anything about what was happening. If we did, we would have acted. If we did, things would have been different. But this is a lie. It was never a lack of German knowledge that failed to stop the Holocaust4, and it is not the guilt of past ignorance, but the guilt of past complicity that motivates the twisted logic of the Antideutsche, the slander of postcolonial scholars as Antisemites, or the silencing and blacklisting of Antizionist Jewish voices in this country – including at the institution where I currently study.

In Germany, guilt has indeed inspired the action of the privileged. It is guilt – the intolerable knowledge that their ancestors were willing collaborators in genocide – that has reduced German memory to a frozen landscape of eternal victims and eternal perpetrators. Today, it is guilt which guards Nazi crimes as a uniquely German topic, ignoring their many willing collaborators across Europe (and indeed the world), and as Michael Rothberg argues, playing into dangerous revisionist histories which strengthen a growing far right across Europe. If guilt is the best mechanism we can imagine for social change, in Germany its limitations are made explicit. What then, are the responsibilities of artists like Sierra who take on political themes in the present? To look for patterns? To raise awareness? Or something else?

Fractal 3: Both Sides

Tap. Clashes. Tap. Tensions. Tap. Conflict. Tap. Looters. Tap. Dispute.

Tap. Both sides.

It is important, when listening to the divisive media these days, not to allow oneself to become overly emotional and gravitate too far in any one direction. When observing (from a safe distance, of course) blockades, riots, air strikes, looting, or police stations burning, it is always best to call for calm from both sides. Remember that it is the middle ground which is the ideal and morally correct position, because it is safely distant from the extremists at the margins – both those who demand the right for ethnostates and carceral borders to exist, and those who demand the right to exist at all. The most rational position between genocide and survival is somewhere in the middle (total extermination is of course quite extreme and therefore to be avoided). Remember that both sides must shoulder an equal share of the responsibility for the outcome of a conflict, regardless of unequal power imbalances that might have led to it. This is how compromise works. Remember too, that it is not a nuanced understanding to offer unconditional support to any one faction, regardless of the need to at least acknowledge said unequal power dynamics.5 It is an unfortunate truth that some colonial violence is legitimate because (realistically) some amount of oppression needs to be considered acceptable; the key is to be able to engage in rational debate about how much. These issues are historical after all, and very complicated, and taking a position on them is always a moral issue, never a structural one.

We must be realistic that the crucial work of reconciliation may be beyond the capabilities of the artist, but in these debates the art world still has much to contribute. When making curatorial decisions, it is important, as Dark Mofo creative director Leigh Carmichael put it in his defense of Sierra’s Union Flag, that the work one chooses “could be seen as difficult from the left and the right, so we find ourselves in the middle”. Finding oneself in the middle means that you will inevitably receive criticism from both sides – a sure sign that one has arrived at the correctly balanced and objective position. Although it may not be popular, this is the ideal location from which to defend oneself against charges that one is silencing free speech, not being sufficiently rational and nuanced, or flatly propagandistic. Ambiguity is after all, the ideal position for art to exist within, lest the artist choose a side and risk their work slipping into tedious and embarrassing didacticism.6

An openness to interpretation by a wide audience is a defining attribute and major strength of the arts. In contrast, propaganda can be easily recognized by its proximity to a strong political position (i.e. moral preaching), which is in very poor taste, both conceptually and aesthetically, and will definitely not get you invited to any cool art parties. It is therefore essential, while gesturing to the privileged, that social or political themes be addressed only in terms of individual actions, best limited to the gallery space or industry publications. Inspiring the viewer to action is best confined to the following areas: consumer choices, voting behaviors, philanthropic requests or a vague feeling of personal discomfort. Power imbalances should certainly never be addressed structurally, lest the guilt one is trying to inspire be misunderstood as a call for accomplices and drags the viewer too far to any extreme. To accomplish this balancing act is the mark of a gifted artist and true ally.

Fractal 4: Real Estate Disputes

Tap. In 1975, Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker officially opens ‘Canada Park’ in the no-man’s-land between the West Bank and Jerusalem. The park is built over the ruins of three Palestinian villages, whose residents were expelled by Israel in 1967. It is a popular tourist destination, and continues to be funded by Canadian organizations.7

Tap. On May 19, environmental group Fridays for Future Canada releases a statement in solidarity with Palestine, connecting the Palestinian struggle to the ongoing colonial occupation of so called Canada, including criticizing the Canadian government’s complicity in continuing to arm Israel. The statement is endorsed by Fridays for Future chapters worldwide, except for the German group, who calls it Antisemitic. The statement ignites a debate in the German green movement in which politicians denounce diverse Indigenous worldviews and place-thought as ‘esoteric bioregionalism’ and Nazi-style ‘blood and soil’ ideology.

Tap. German Culture Minister Monika Gruetters praises the recent German decision to return Nigeria’s Benin Bronzes, looted by the British in 1897 (over 500 of which are housed in the newly opened Humboldt Forum in Berlin), as contributing to “understanding and reconciliation” between the two countries.

Tap. What is happening in Sheikh Jarrah today, the Israeli foreign ministry informs us, has nothing to do with ethnic cleansing by a colonial power, but is merely “a real estate dispute.”

Here in the heart of empire, our streets are named for both colonizers and Karl Marx. Here in the heart of empire, the denizens of culture finance both Israeli rockets and the restaging of colonial violence as postcolonial critique. Here in the heart of empire, you are free to argue for the return of looted artefacts, but not for land return (from the river to the sea, on Turtle Island, or anywhere else). Here in the heart of empire, #noborders extends only as far as the edge of the West Bank’s apartheid wall.

In defense of the cancelled Union Flag project, Sierra invokes a long history of criticizing nationalism and support for decolonization in his work. His 2015 project Black Flag, in which Sierra organized the raising of what he calls “the anarchist black flag” at the North and South pole “to occupy the world,” is to be properly interpreted as a decolonial rebuke of nationalism. Thus, through the alchemy of the artist’s good intentions, the colonial gestures of planting a flag or drenching a colonial symbol in Indigenous blood are transformed into serious decolonial critique.

“This is what settler colonialism does”, Laleh Khalili writes, “it turns land, a piece of living and loving, a sacred milieu, one to which the Indigenous inhabitants have an intimate connection into property”. On this, the Israeli and Canadian governments, Marx8, the German green movement, and Sierra are all in agreement: land is mere resource, raw material, inert object to be claimed (according to political preference) by nationalists or anti-nationalists, white supremacist Germans or Antideutsche, capitalists or communists, all with the same commitment to occupation and conquest.

My ancestors arrived on Turtle Island as colonizers from Scotland (1819), Denmark (1928), Germany (1800s), and certainly other places that I have no record of. But colonization is not a list of dates marking conquests and arrivals. It is not history. Colonization is an ongoing relationship that encompasses both the human and nonhuman world, relationships “formed and maintained by a series of processes for the purpose of dispossessing, that create a scaffolding within which [Indigenous] relationship to the state is contained”.9 Under the colonial state, land is turned from relation into mere property10, ancestors become objects, and (if you’re talking to any Marxists) dispossession is flattened to proletarianization.

It is not a coincidence that the colonial Australian, Canadian, and German governments all use exactly the same word when referring to the present inconvenience of looted ancestors and looted land: reconciliation. It is always reconciliation, rather than Indigenous sovereignty or land return which marks the limit of the liberal colonial imagination. It is always, in the words of Hermann Parzinger, head of the Prussian Cultural Foundation, “coming to terms with colonial injustice” that marks the horizon of colonial efforts – Vergangenheitsbewältigung – coming to terms with the past.

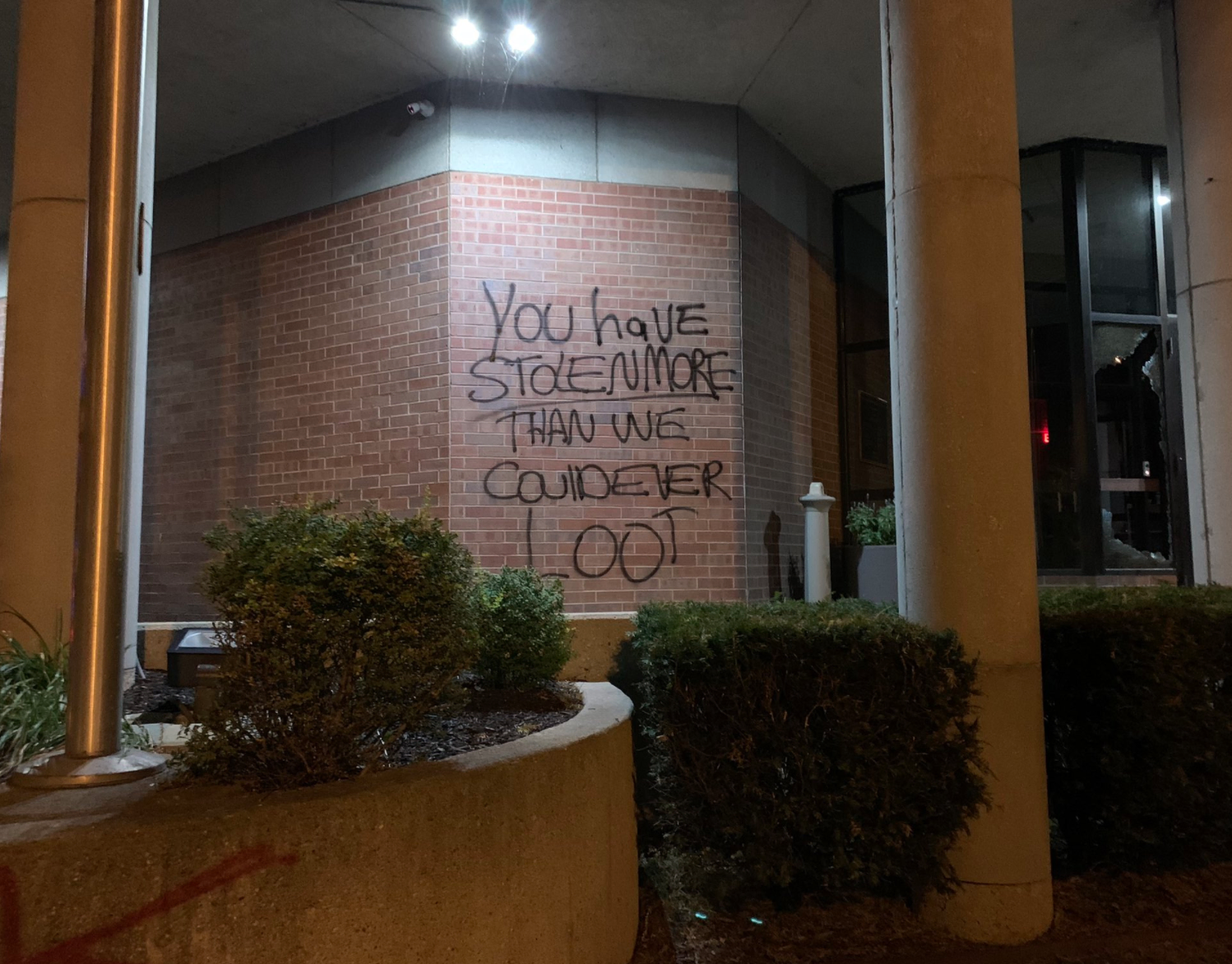

In Germany, the past is also a real estate dispute. In the settler colonial imagination, the past, like land, is a location; merely property waiting to be owned, traded, or mastered. And like property, memory of the past must also be governed by the rules of the capitalist marketplace, a zero-sum competition for scarce resources. “The Hallmark of liberalism, the form of thinking par excellence of the economy”, write the Dispositions Collective, “is to make competition the only acceptable mode of antagonistic relationships.” As such, memory – like looted ‘objects’, like land – must be hoarded behind national borders and into colonial museums by the all knowing white possessive.11 Behind these borders, only the right type of Germans have the right to pass judgment on their memory culture; define the correct emotional attitudes when discussing it, and act as the sole experts in its display and curation. In the zero-sum colonial imagination of scarce resources, there is no space for entanglement of memories and the potential multidirectional solidarities such entanglement might produce.12 Behind these border walls of institution and nation, the dispossessed continue to be objects of possession. As artist Shellyne Rodriguez, who organizes with Take Back the Bronx, put it in a recent talk for Strike MoMA: “Behind the vitrine or behind bars, these are the root of our options.”

In his recent Berlin project The 3 Commandments of Postcolonialism, Sierra seeks to engage the current debate on Berlin’s ethnographic museums by cataloguing the economic value of Museum Island’s marketable assets while simultaneously proclaiming “Stop the stealing. Return the Stolen. Compensate the victims” on a public plaque. This work, he argues in his defense of Union Flag, is another clear example of his support for decolonization. Again, as with the colonial state, relationship is transformed into real estate dispute. Not listening. Still not listening.

Can what has been stolen ever be returned, as Sierra proclaims? Can the scale of the violent and ongoing loss ever be compensated? The revolutionary potential of the entangled histories imagined by decolonial Indigenous organizers is not merely in property changing hands (moderated exclusively through the correct colonial channels), but in upending the colonial worldviews that define land, ancestors, and historical memory as property to begin with. “Under the museum, under the university, under the city,” a recent Strike MoMA banner outside the Museum of Modern Art in New York city reads, “the land.”

Fractal 5: Accomplices

In English, guilt does not pack the same ideological punch as the German Schuld, which combines guilt with fault, debt and obligation. The struggle in Germany today is not only to overcome German guilt for the atrocities of their ancestors, but to overcome the understanding of colonization as historical, and the colonial state as predicated not only on absolute claims to historical ancestry, but on the type of relationships it upholds and maintains. It is the struggle to reclaim the revolutionary potential13 of debt from the liberal quicksand of guilt, and to reimagine the better world our debts to one another might build.14 This is what German discussions on Palestine and decolonization more broadly do not address, and why Sierra’s work continues to be appreciated as radical social critique rather than what it really is: a fundamentally conservative reflection of the shallow colonial imagination.

What then, is demanded of the guilty on the European continent like Sierra? Like myself? Austrian-Belgian Auschwitz survivor Jean Améry argued that the proper attitude of Germans after the Holocaust should be one of Selbstmisstrauen, or “self-mistrust.” In making art, in writing these words, I look for the fractal patterns:

Tap. The ease with which I might turn relation into property or take what is not mine to claim.

Tap. The prestige I might accumulate by merely pointing at injustice.

Tap. The powerful audience I might find who would agree that my intent is more important than my impact.

Tap. The acts I might justify, believing in the power of guilt to liberate.

Guilt, which always centers the powerful and closes off the potential for messy solidarity with the safety of tokenism, is not the same as Selbstmisstrauen. Selbstmisstrauen is an opening and a constant reminder that it is through our actions that we must continually make ourselves accountable. It is a reminder that our politics are located in our everyday social relations – in relationship, not just the ‘correct’ analysis, or the clever artistic gesture. It is not a lack of knowledge that is a barrier to action, but the ways in which the already powerful marshal their substantial resources to defend their vested interest in maintaining violent systems of inequality. Decolonization is not “occupying the world” in the name of anarchism or the arrogance of making postcolonial commandments for which one is accountable only to grant funders, festival curators and entrepreneurs, and it is not a white settler artist writing essays in Berlin.

I am not the descendent of German Nazis, but of European colonizers to what is currently Canada. I am able to study in Germany today because I am the beneficiary of racist, genocidal segregation policies that still govern colonized Turtle Island, policies from which the Nazis learned much and which still inspire apartheid regimes today. My debts are also unpayable. I hold at the front of my mind Susan Sontag’s warning that “No ‘we’ should be taken for granted when the subject is looking at other people’s pain”15 I hold at the front of my mind, a commitment to abolition that is grounded in the belief that none of us are disposable, and that the demand for uniquely evil perpetrators or perfectly sympathetic victims is also violence. We, the beneficiaries of the horrific acts of our ancestors, are also not disposable. To act in true solidarity, to dismantle the structures they have built for us at the expense of so many others – to do more than merely gesture at atrocity – we must believe it.

Art has the power to go so much further than any gesture towards the Documenta set could ever offer. It shapes worlds. In these teachings I am indebted to the work of Black and Indigenous revolutionaries and thinkers like Sylvia Wynter, who argues it is our capacity for symbolic storytelling which makes us uniquely human16, and Gloria Anzaldua who understood that “Nothing happens in the ‘real’ world unless it first happens in the images in our heads”17. They have taught me is not the guilt of the privileged that shakes the foundations of empire, it is the revolutionary power of the stories we tell ourselves in building our collective power. It is our interwoven, repeating fractals of memory and resistance – not as property, but as cross pollinated seeds of the radical imagination that are the foundation of a better world. Those are the patterns I am watching most closely for.