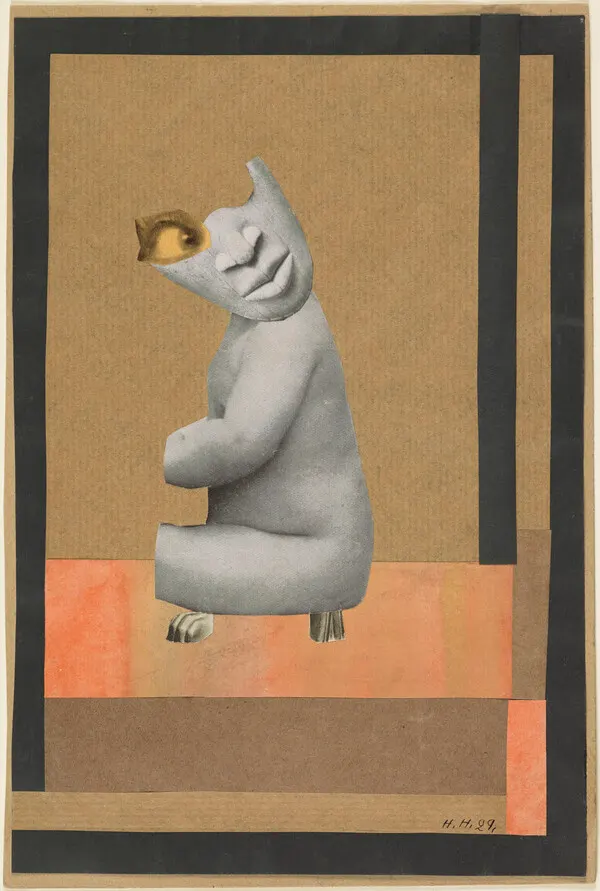

A photomontage by Hannah Höch entered the Edinburgh holdings of the Scottish National Galleries in 1995 through the bequest of marmalade-heiress Gabrielle Keiller. This belongs to the series From an Ethnographic Museum (1924–34), which was most complete in its presentation during the artist’s solo exhibition in student housing for Masaryk University in Brno, Czechoslovakia, in 1934. There, ten works from the series were exhibited, with the show’s organiser, František Kalivoda, elaborating the “combative and playful” aspects of photomontage as a contemporary medium in his accompanying lecture. In a rare statement issued in tandem with her first solo exhibition, five years before, Höch herself suggested that such strategies were deployed with an agenda: “I want to blur the fixed boundaries that we people have drawn around everything in our sphere, with obstinate self-assurance…” Speaking from the Hague in 1929, the artist’s invocation of “we people” presumably names European society, implicating herself in a dominant culture that she otherwise unnerves. Yet, questions remain over how permeable at home, or rapacious abroad, “our sphere” might be—indeed they hover over the need to possess a sphere, to claim ownership of a realm, at all.

To make the works in this series, Höch used strategies learnt from looking at ethnographic museums. She plundered illustrated journals of the 1920s, typically for images of either idealised European womanhood, or objects looted through European colonial violence. Then she decontextualised her plunder, splicing them together for her own display purposes—producing a series she dubbed “der Sammlung”, or, “The Collection.” Does her work critique or repeat harm in the name of the ethnographic museum? Given the impossibility of doing both simultaneously, it does neither: harm is only in the background. At the forefront of her project is a messing-with, a limit-pushing, a desire to elude and confound.

The Höch collage in Edinburgh is usefully thought in relation to its companions—with sister works housed most salubriously in New York and Paris—but it is also particular. For me, it exposes the wanton, freakshow cravings that lace the museographic display in Europe of booty from Africa. The torqued figure, set on a pedestal but not quite contained by the prison bars, is a creation of modernity, coloniality and capitalist patriarchy, which is doomed to a monstrous form by those entangled forces.

Nazi vilification of Höch’s art as “degenerate” would seek to quell her monster forms without addressing their galvanising energies.

How do we flex critical possibilities through Höch’s work today?

*

The Scots-Ghanaian artist Maud Sulter perhaps saw the Höch collage in a 1988 exhibition of Keiller’s collection in Edinburgh. Certainly, Sulter’s Syrcas, a photomontage series from 1994, is (amongst other things) a response to From an Ethnographic Museum. In the bibliography for her Syrcas publication, Sulter notes Maud Lavin’s book Cut with the Kitchen Knife: the Weimar Photomontages of Hannah Höch, which had come out just the year before.

Syrcas reignites the transcultural fireworks to be detonated through collaging photographs. The public forum invoked by Sulter’s title is not the ethnographic museum, however, but the circus—syrcas in Welsh, as spoken in the country of the commissioning institution, Wrexham Library Arts Centre. Images of objects looted for museum storage afar feature powerfully in the collages, but the emphasis lies on their being at large in the complex lived juxtaposition and entanglement of European and African visual cultures. Comprising sixteen works across five carefully composed clusters, there is a density and orchestration that belies synoptic visual analysis. The circus theme, which is elaborated most explicitly in the accompanying poem, Blood Money, draws on another series of works produced in Germany at the same time as From the Ethnographic Museum: August Sander’s 1926 photographs of circus artists, usherettes, labourers and their families, a troop uniting different racialised identities, pictured in Köln not performing or otherwise at work but in their down time, as a part of his project “Citizens of the Twentieth Century.” This work, in book form, also features in Sulter’s bibliography for Syrcas. Of all the ethnicities invoked in Blood Money, ‘Celt’ and ‘African’ come closest—between them—in summarising the artist’s own heritage.

Syrcas reverberates with many such pluralities, which both thrive and struggle to survive within European nation states. Picking up on something of Höch’s own line of enquiry, it reels with the impossibility of any art canon, or canon of beauty, ever being adequate to the essential extravagance of cultures.

Höch had access to off-prints of the journal Der Querschnitt, which she routinely snipped into for her research and art. With more strategic violence, perhaps, Sulter gathered much of her source material by mutilating a book: the only one in the World of Art series that centred African practices. This publication was written by the director of the Hunterian Museum, in Sulter’s home city of Glasgow, where the “ethnography” collection has since been renamed “world cultures.” Perhaps the Sowei figure collaged in black-and-white reproduction on top of a tinted postcard of a placid Alpine scene, in Syrcas: Noir et Blanc: Trois, offers her sister figure in the Hunterian collection a narration of their shared predicaments and possibilities. Having been “dropped out of history” by the infamous European “exhibitionary complex” of the nineteenth century, so as “to occupy a twilight zone between nature and culture” (to quote Tony Bennett), they may now—in holding precisely that space—exude a newly compelling power for those upon whom the costs of seeking to disconnect from nature, in order to manage and monetise it, are finally dawning. In Noir et Blanc: Trois, the carved headdress is as monumental as the Alps and exceeds the landscape’s frame, standing proud, while the pine trees below hint at the raffia costume of a gathering performance by the Sowei who may yet bring on, spiritually, a new and transcultural generation of females.

Sulter was not so interested in her small, papery originals for Syrcas. She photographed these and made large-scale prints for the purposes of exhibition, such that the figures and figurines she included approached life size—addressing us as bodily equals in the gallery space. The violence of her action with scissors on that African Art book should not overshadow the care simultaneously taken to maintain the integrity of the photographed objects she liberated.

After touring the UK as a solo show, Syrcas was circulated to the first Johannesburg Biennale of 1995. In South Africa, surely the pictures looked European and the poem sounded English. The continental shift must have also inverted the references in the work: the stolen objects photographed came closer to their homes; and the rural landscapes pictured moved very far away. The Johannesburg building in which Syrcas was exhibited, the Electric Workshop, brought industrialisation powerfully into its cultural frame. In her review for Third Text, the artist Candice Breitz writes of the space in a way that opens up the operation and affect of Syrcas in particular:

“Unlike the Museum Africa, a venue which is characterised by the sanitised ambience we expect of museums, the Electric Workshop speaks unequivocally of labour and decay. It is an industrial warehouse complete with hanging cranes, dusty alleys, unfathomable nooks and crannies and no pre-existing divisions which could be used to separate exhibitions. Its chaotic sense of violent fragmentation and architectural anarchy is both melancholic and disturbingly moving.”

Yet there is also something forceful and positive about the riotous comings-together in Syrcas.

*

The work in Höch’s series From an Ethnographic Museum held by the National Galleries of Scotland excerpts the lower half of an especially famous face. From the eye sockets and bridge of the nose downwards, we see Iy’Oba Idia, who lived c. 1490–1540 in the royal court of Benin, carved there in ivory around a century later. Höch could not have known she’d taken her scissors to the Queen Mother, as her image had not yet been identified in Europe, given the lumping in of this effigy amongst Britain’s amassed spoils of colonial war.

The face of Idia was brought back into active function, channelling ancestral powers in a new ceremonial occasion, through FESTAC, the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture staged in Lagos in 1977. As recently articulated by Chimurenga’s publication dedicated to that event:

“Part restitution of looted, centuries-old heritage and part conspicuous consumption fuelled by a booming petro-Naira, the flood of Idia images that attended FESTAC constituted a potent decolonial move and a brilliant branding project all at once. Untethered from her home in captivity and replicated over and over again in the land of her ancestors, Idia was deployed by the Nigerian Government to tell a very particular story: the story of a nation destined to act as a beacon for all black people and as the economic powerhouse of a global south shorn of its colonial shackles. Recast as a clarion call to the oppressed by a military dictatorship in thrall to the capitalist system undergirding this selfsame oppression, she emerged as a powerful tool of hegemony in the hands of the Obasanjo regime. Rarely has instrumentalization of art to political ends been handled with such brio.”

I come to the Höch collage in Edinburgh post FESTAC—or, rather, following my understanding of FESTAC from the “cultural kaleidoscope” offered by Chimurenga (to borrow a description from curator Elvira Dyangani Ose). As such, I find the British Museum—but not global capitalism—has been exorcised from the work, leaving a face whose fracturing conveys the scars of the one and ongoing subjugation by the other.

*

In On the Periphery (1976), Scottish poet Veronica Forrest-Thomson ventures a “Conversation on a Benin Head,” yet she is snagged by Macbeth’s dagger and R. D. Laing’s knots (neither of which matter if you don’t know them; but, if you stay in Scotland, you may). I hide behind her freestanding line in the middle of this troubling poem: “Whatever it was I didn’t do it.” Not even a comma is allowed to pace this defensive move, which remains blurted. Yet her preface to the poetry collection it sits within is more measured and rousing. A call to arms, it urges the taking and making of art into ‘a new and serious opponent—perhaps even a successful opponent—to the awefulness of the modern world.’

*

With its central figure the product of collaged visuals from reading material, the work by Hannah Höch is maybe most happily consulted one–to–one in the prints and drawings room in Edinburgh—or online, invited into your personal space. As such, it is somehow less captive to the avid alien gazes that it arguably puts into question, yet risks reproducing when framed, glazed and hung formally on a museum wall. I offer the work here as a guest—and you, if you choose to stay with it, will decide upon how engaging it might be.