I probably know more about Henry VIII—that corpulent, extravagant, serial monogamist—than many of our own larger-than-life monarchs. My parents sent me to boarding school in Edinburgh when I was six years old, so I missed out on a lot of the local lore. On returning to Nigeria, I had to address the gaping holes in my knowledge of the country’s history and bring myself up to speed. But my reason for invoking Henry VIII here concerns his most widely-used legacy. Not many people know that it was his habit of fastidiously binding important state documents with red ribbons (or tape), that has led to today’s euphemism for bureaucratic excesses.

Against the backdrop of Aimé Césaire’s view that poetry is an effective tool in affirming cultural consciousness, it is broadly understood that The Arts are a powerful means of expressing and conserving cultural authenticity. But what does one do when the vehicle for the propagation of Culture is stalled by a pernicious colonial imposition—bureaucracy, that is, Henry VIII’s “red tape”? It is pernicious precisely because of its utility and power, and it was bequeathed by the colonial masters in their effort to order our affairs and manage our ebullient societies to their benefit.

Faced with the challenges of independence and post-colonialism, we proceeded to apply red tape indiscriminately to all sectors of society. Our civil servants reigned supreme, wielding their new powers, not realising that creativity, expression, and matters of the soul and heart required nothing more than freedom, a lack of constraint, exuberance, and optimism. All powerful motivators, yet, so easily stifled by red tape.

If, as Césaire says, poetry is pre-scientific, then creativity is ex-bureaucratic. To understand this in its most potent form, one need only look through the window on the web into the minds of the ‘soulless’ superintendents of Nigeria’s creative heart. The very word ‘bureaucracy’ proclaims its enervating quality—the very opposite of the energy it should channel. The edifices of officialdom stifle creativity by their very existence: “Federal Ministry of Information and Culture!” Orwellian in the eager precedence given to ‘Information’. Culture is an afterthought, an add-on, a mere distraction from the important task of spinning and PR-ing and orienting the people towards the hidden agenda of the non-cultured powerful.

On the official ministry website, we find a sterile presentation of our culture. One imagines a middle-ranking bureaucrat, steeped in civil service conformity, attempting to capture Nigeria’s cultural essence on a page in cyberspace. Burdened by ennui, ticking a box on the sitemap of banality, working to deliver another item constricted by the ubiquitous red tape that binds even cognition. Stifling a yawn, another traditional titbit is added—a festival that a tourist might deem worth attending, or an out-of-date catalogue of painters, authors or entertainers. Slightly more inspired, the bureaucrat sifts through a pile and selects a colourful, cliched picture of a grinning dancer with a chalk-lined face and a grass skirt, to feed the decades-old, foot-pounded, drum-beaten stereotype of a happy African doing what Africans do.

The website is a visible symptom of systemic malaise, a misguided attempt to bureaucratise rather than enable culture, a blindness to the reality that a nebulous national essence cannot be grasped, let alone encapsulated by a bored bureaucrat with broadband. It cannot be shaped by the blunt instruments of governance nor packaged and presented in the language of policy and planning.

A co-parent of Negritude, Léopold Sédar Senghor outlined one of the challenges African nations were faced with as how “to access modernity without trampling on our authenticity”. Trampling, stifling, ignoring, misrepresenting—there are many ways to carelessly squeeze the life out of our authenticity. What can’t be done is to mandate it back into existence.

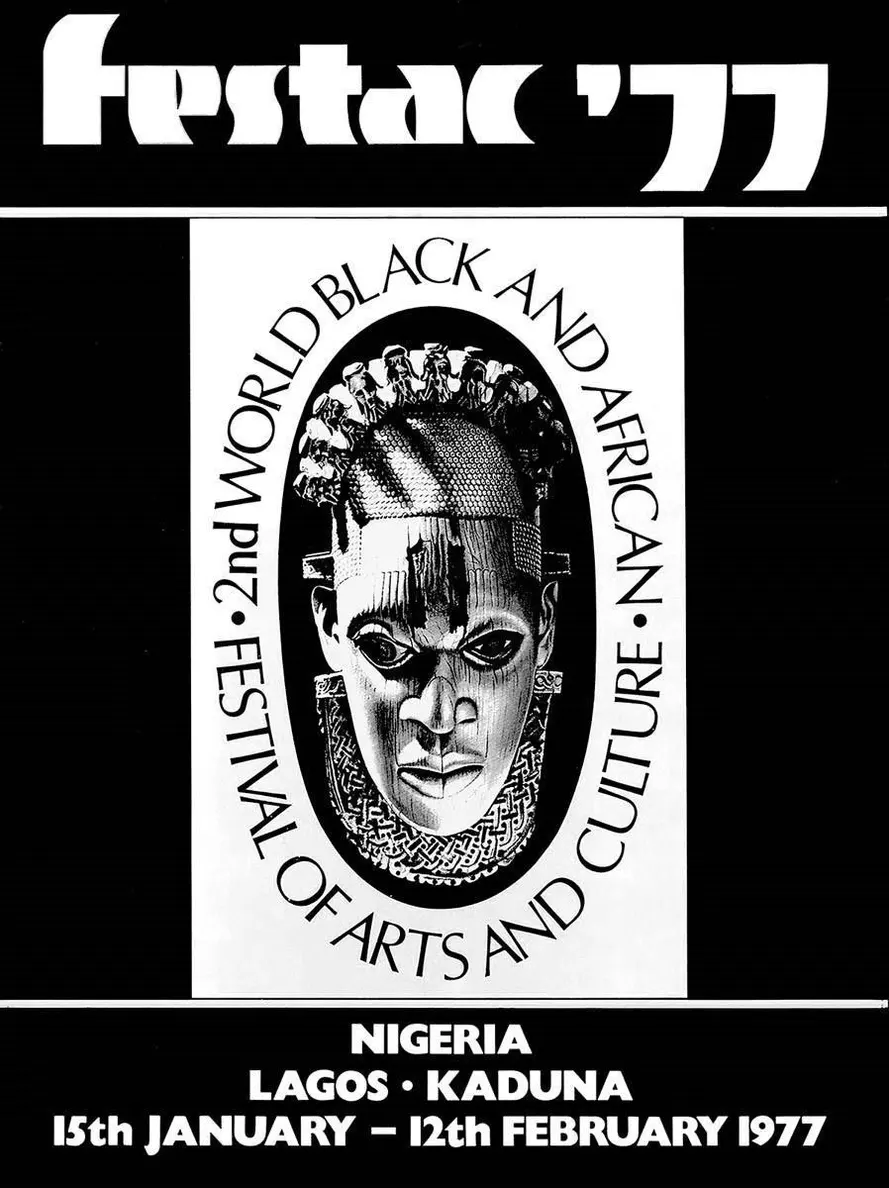

The Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, also known as FESTAC ‘77, provides a sorry yet instructive tale. The first edition was held in Dakar in 1966. With colonies becoming sovereign nations in quick succession, the twin waves of Afrocentrism and Pan-Africanism were swelling, and along with them, our collective chests. Pride and self-recognition buoyed our creative spirits and the plans for the second edition of an ambitious cultural exposition were set in motion, aiming for a Lagos extravaganza in 1970. First a coup, then the civil war intervened (ominous signs of our dangerous postcolonial flaws), but eventually, three weeks in 1977 were set as the new dates. As planning progressed, clashes of style and sensibilities emerged. As Senghor might have said, it was “un-decalage”, with artists from Fela Kuti to Wole Soyinka voicing major concerns. It was clear to committed cultural players that most of the myriad cultural seeds sown would die off in the boardrooms of government ministries.

One cannot spend the millions that the project consumed and not make a splash. It is impossible to bring together thousands of writers, academics, and artists to participate in film screenings, drama and music productions, daily colloquiums, durbars, regattas yet fail to generate numerous sparks of genuine creativity. It is impossible for Black artists worldwide to converge and not anticipate an explosion of Black and African culture on the world stage. This was also a major infrastructural project—a FESTAC village was built to accommodate 17,000 participants, which was nothing compared to the handsome 5000-capacity National Theatre, complete with conference facilities and cinemas. Fleets of luxury coaches were purchased for the comfort of the thousands of visitors. Across the country, the bureaucrats rushed half-baked projects to the fore. As long as these projects had a FESTAC tag, they could lay claim to a line in the budget and become part of the grand show.

The star of FESTAC burned brightly for some weeks, and then came the inevitable anti-climax. Post-festival plans were thin on the ground. The Arts had enjoyed fleeting global limelight, Nigeria had gained many new friends but the majority moved on. The National Theatre was abandoned to slowly crumble into disrepair, a metaphor for the trajectory of the Arts under successive Nigerian military administrations. Even the treasure-trove of donations of artefacts and gifts from 5 dozen countries (to be held on trust for Africa) were reduced to fodder for the civil servant’s files. Documented, described, and carefully put away—the files bound with red tape.

To accommodate the artefacts, The Centre for Black and African Arts and Civilization, CBAAC, (one of the parastatals overseen by the FMIC) was established by military Decree No. 69 of 1979. It remains a lifeless repository that makes no pretence of living up to the ambitions of its founding principles of “promoting and propagating Black and African Cultural Heritage.” It exists in a large grey edifice in Lagos Island, the drab façade enlivened only by colourful zigzag patterns on the pillars that frame the front door. These weak embers fall short of the expected wildfires that we hoped would set the continent aflame. You cannot mandate culture into existence. Of course, culture cannot die out. While there are humans, Culture will find light, flow through time, meandering and changing in profound ways in obeisance to invisible laws. After FESTAC ‘77, keepers of the national authenticity of a country of (then) 67 million stretching from the fringes of the Sahara in the North to the ocean-soaked southern beaches, are still stubbornly finding means of creative expression in the face of national economic decline and misgovernance. Northern Nigeria presents a recent example of such resilience. A Governor dispensed with red tape and invited Book Buzz Foundation to curate an annual book festival in 2017. Mostly state-funded, and importantly with little red tape involved, the creatives were given the space to do what they do best. The inaugural edition of ‘KabaFest’ showed how hungry Northern Nigerian youth had been for a platform to express themselves creatively—to perform poetry, discuss literature, listen to music and browse the visual arts. Since then, inspired by Kabafest, nine book festivals have emerged in some Muslim-majority, hyper-conservative states. Initiated by lovers of Culture, in tune with local sensibilities, they are pushing the boundaries, exploring, creating and interacting. These gatherings that celebrate poetry, literature, drama, and other art forms are a testament to the doggedness of private citizens who understand the value of the Arts and its capacity to be a vehicle for cultural authenticity.

More than ever, then, we seek an administration that understands the value of cultural expression, and how to create space for it to flourish. Economics aside, there is also the problem of technology. The symptoms of cultural cachexia are beginning to show, with social media encouraging a dangerous trend of superficiality and an inverted value system. A generation that is used to fishing for ‘clicks’ no longer has the metrics for judging merit. Creativity does not pander to cheap ‘likes’, but that is becoming the currency of online existence. We are reverting to the base instincts that we have tried to shed on our journey to postcolonial cohabitation.

Hiding behind their screens, we resort to easy violence, celebrating it, elevating disrespect, shock, and impunity. Creativity is diverted to the invention of crude pranks, cruel insults, or the unfiltered raw exhibition of private life turned into public performance—the more dysfunctional the better. Everything is measured by clicks. The playing field is tilted towards the crass.

In the midst of all this, the civilising influences struggle, leaving poets, visual artists, performers, musicians, authors, and creative pioneers to fight for the attention of a dwindling number of patrons. From time to time the stars align for a few and they gain exposure or ‘go viral.’ Like the Ghetto kids from a deprived rural neighbourhood in Uganda, fired by innocent joie de vivre and a captivating modern rhythmic talent, they danced their way to internet fame. Or the Nigerian video makers who turned the concept of objet trouvé into imaginatively cloned scenes from Hollywood hits, with every vignette matching the original, act for act, word for word, except the set and props are mundane, upcycled objects. Their inventiveness rewarded, the Ikorodu Bois have been adopted by generous do-gooders and they deserve nothing less. Such stories bring a warm glow to the spirit, but they are a cause for optimism only in the way the first green shoots in a scorched field remind us of what has been lost. When a country has not developed a means of identifying and nurturing creativity, even the talented are left to the mysterious algorithms of TikTok or Instagram and the random confluence of intangible forces that constitute virality. But culture cannot thrive on virality alone. There must be a system, and that, unfortunately, is the domain of diligent bureaucrats.

Each of our 37 states has its “Ministry.” Taking the lead from the FMIC, they are rarely granted full status, instead, ab initio, they are bundled with other ‘leftover’ sectors: Tourism or Youth, or Welfare or Women’s Affairs. Not mature enough to exist on its own, ‘Culture’ must hobble along, twinned by fiat. An ironic thought occurs to me; perchance Culture would fare better if it were shackled to all ministries—a reminder to all that, in an ideal world, every sector should be charged with infusing national authenticity into their policies. Each hemi-ministry performs similar official role-fulfilment, after the list of cultural treasures has been drawn up, the half-hearted fight for a chip off the new budget begins. A plea for maintenance (pest extermination, painting, roof repairs, or shelving), replacement costumes, transport, or rehearsal fees. Then—slightly higher on the excitement scale—there is the duty to add a dash of ‘authentic’ culture to official events. This will usually involve dancing and drumming, or occasionally a drama sketch, which will also include dancing and drumming. Occasionally, there is a surprise that pushes the boundaries, something new, arresting and genuinely inventive. Invariably, it is a talent or group of talents that have defied oblivion and demanded the attention of officialdom by their sheer creative force.

Poetry is well-placed to invade such rare spaces. Give them an inch and they will give you a verse. We run a monthly Open Mic event at Ouida Lagos, and our space can no longer accommodate the throngs of young people who are using their talent to articulate their joy, triumphs, trauma, or hopelessness. They come together and speak up for the typical Nigerian who is just trying to survive and thrive, in the face of adversity. We desperately need those who can sum up our anguish, commit it to a page or release it on stage. We need the special language of poetry to fight for access to our culture, to reject not just the alien but the homegrown impositions that are nevertheless alien. We need those who will write over the red tape and release Nigeria’s creative potential.

So dear bureaucrats of Black Africa, we need you, but we need you to understand that our culture is not only being reined in by the colonial museums hoarding our plundered artefacts, nor by the universities and cultural institutions who have given our poets, writers and artists a place to flourish, nor by the publishers abroad who get to call the tune because it is they who package our wordsmiths. It is not they who pay lip service to Culture and have reduced our authenticity to drums, grass skirts and daubs of face paint. It is you: our rule-bound, conformist, risk-averse bureaucrats who do not grasp the sacred and profound duty you have, and have no idea how to discharge it. And when, despite this, Culture, authenticity, creativity and talent manifest, do not strangle them with Red Tape.