While every conversation between Arabic speakers has to start with the question How are you?, even if one is on their deathbed, when a Palestinian is asked How are you?, one expects to be answered: Perfect, God is to be thanked, or, Unwavering. None of this, though, discloses any information as to how one is, in fact, doing. But there’s That is. At odds with its total incoherence as an answer, ‘that is’ is the closest someone can get to confessing that things are difficult. Why, what happened? I ask Almaza, a friend from Jerusalem, as she opts for That is. She was fired from her job of ten years as a receptionist at a Palestinian mobile phone company, or, as she soon adjusts her answer, was encouraged to resign.

To the question of what she is doing now, she giggles before answering: Crochet, sister. The answer feels out of sync. It does not correspond to the image of Almaza that I have. I don’t comment out of politeness, perhaps, accepting the fact that people may change. I try to understand the course of events before this ‘crochet’ moment erupted. I ask why the company fired her, or ‘encouraged her to resign.’ She answers with a single handed stroke of her hair, pulled back in an undyed ponytail, and a smile.

Almaza details her five year saga with management trying to get rid of her. They deemed her too old to be a receptionist; the face of the company, welcoming customers. Initially, she refused to resign, despite management’s attempts to marginalise her by freezing her annual raise, bringing a younger employee to sit next to her on the small reception desk, placing her desk next to the main entrance of the company, as if she’s a guard not a receptionist, trying to find mistakes in her work, unofficial meetings asking her, politely, to leave, but nothing would shake her. She loved her work; she loved dealing with people, she loved solving problems and calming angry customers, the buzz around the reception area. Such pressures even brought her to think of creating a World Receptionists’ Union, to defend their rights and attend to their needs. She was determined not to budge, even ready to fight head on. She threatened to reveal their sexism and ageism, to bring them to court, to expose their actions to the press. But after a few years of resistance, realising that the world is dirty and her being a single person against a huge international company, she gave in. It was only when, for the third time, that management sought to persuade her to leave, that she felt the weight of being unwanted and unwelcome in a place that she gave the last decade to.

Almaza would spend three to four hours a day on the road from her home in Silwan, Jerusalem, to her office in Ramallah and back, with a couple of hours spent waiting at Qalandia checkpoint along the way. Sometimes she’d spend three hours on the way back alone. Driving a car with a stick shift only to move thirty centimetres every few seconds had me suffer immense pain in my back and legs. But manual cars consume less fuel, which is vital with a low salary like mine.

Almaza says she’s attached to her car, before adding this is perhaps her problem: she gets attached to people, to work, to things, though more often than not, these attachments only ever bring about disappointment.

How do you spend your days now, then? I ask. She sets her alarm for six in the morning as before. She wakes up, drinks her coffee, then listens to the radio programme she used to when she drove to work, where interviews and political commentary on the situation in Palestine is commingled with songs. Now, she would walk around her small studio apartment for its entire duration. She then reads the news for a while before heading to her elderly parents’ home, which is nearby, has a late breakfast with them, and starts crocheting until the afternoon, wherein she returns to her flat to read, fix dinner, then head to sleep at ten. She does not see many people. But she sticks to her daily routine so she does not slip into depression or despair, or worse, insomnia: I need to go to sleep and wake up in these times, also out of fear of insomnia. She explains she became an insomniac for a few weeks after she lost her job.

The history of insomnia is long in Almaza’s life. It started when she lost her children. Almaza got married when she was seventeen years old. She had two kids then asked for divorce a couple of years later. It was agreed that she retained custody. After three months, when her kids went to visit their father, they weren’t allowed to come back. There were no Palestinian courts to go to, and she didn’t want to go to the Israeli courts responsible for incarcerating Palestinians, including her brothers. Thus began Almaza’s most painful experience, accompanied by years of insomnia; an experience that would shape her life in ways she could never have anticipated.

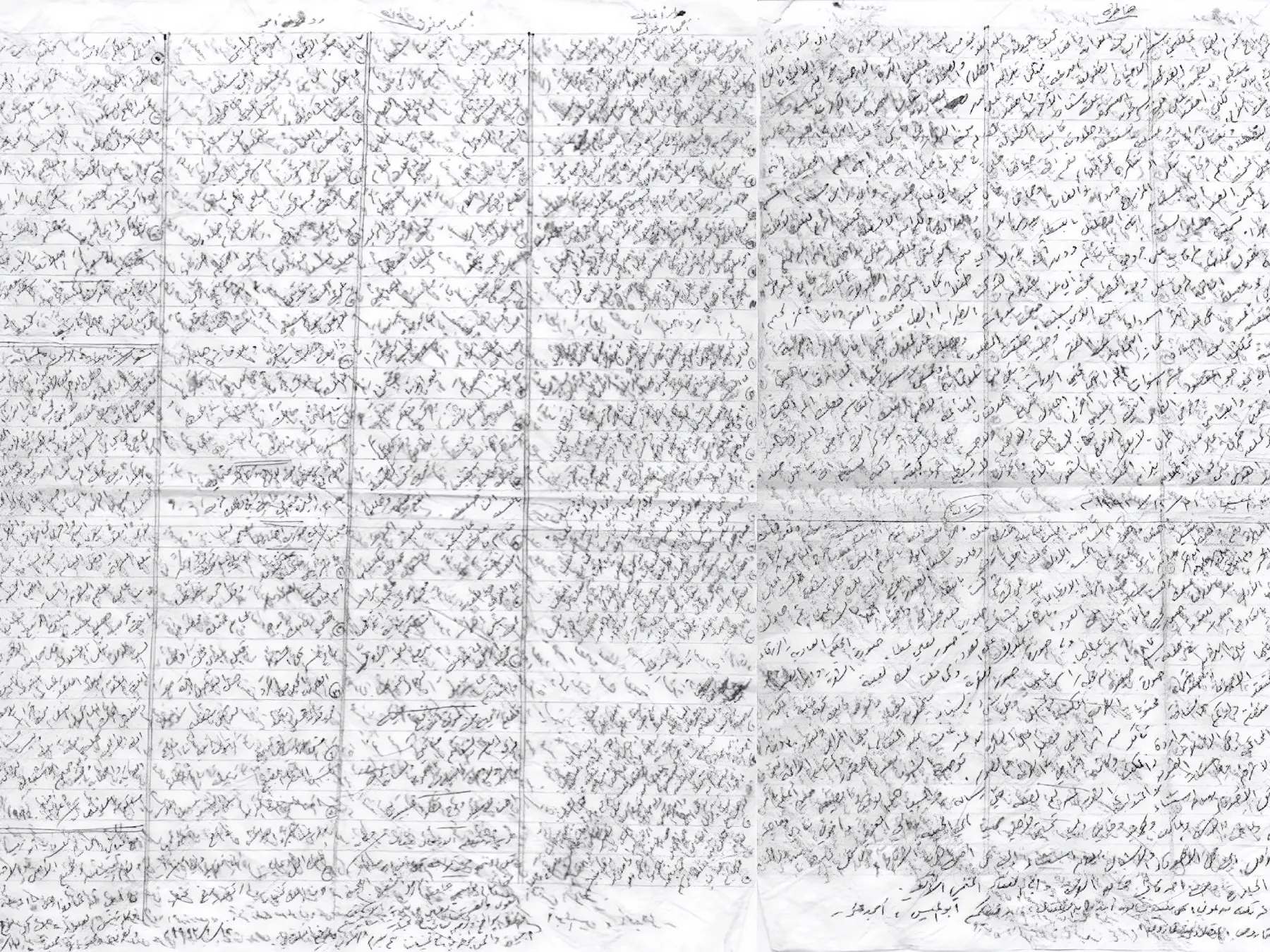

Early on she realised she needed money to buy a car so she could get her children to visit her. She also needed money to spend on them. This saw her going to her family to say she wanted to work. After resistance, they accepted. At the time, a woman had two possible jobs, as a seamstress or a hairdresser. She hated both and couldn’t imagine doing either. But she thought of it as a start. She joined a hairdressing course, and halfway through, she left to join a course on computer literacy, which included skills in typing. It was a new field, then, and she discovered it as something she liked. Eventually, this brought her to work as a typist in a press office run by a group of Palestinian Marxists. This coincided with the uprising of 1987, where her job was to collect news reports from journalists across Palestine and subsequently transcribe and assemble them into a news bulletin. She describes how she would call the mayoral offices of small villages and towns to collect such news. Until the late 1990s, Palestinians weren’t granted permission by the Israeli occupation authorities to get phone lines. The exception for this policy were mayoral offices, as mayors were appointed by the Israeli intelligence services. Almaza would wait on the line until someone fetched the journalist, then proceed to type the news. She recalls her actual difficulties with writing, given that she left school quite early on, in the eighth grade. At that job, Almaza also met G., a Jewish-American leftist who came to Palestine after she and a Palestinian Marxist fell in love. G. would soon turn into a member of Almaza’s family, and Almaza’s best friend. They both worked hard in the office, spreading news of the uprising to international outlets, until their work came to the attention of the Israeli authorities and the office was forced to shut. Left again with no job, Almaza joined, with G., a Palestinian women’s union. G., at the time, encouraged Almaza to study sign language, a field in which G. specialised. It was, during this period, too, that Almaza began a struggle with her father. She desired to remove the headscarf she had to put on when she got married. Her father said this could only happen over his dead body. Almaza thus began a series of at-home protests, carrying around cardboard signs demanding permission to take off this headscarf, then a series of strikes: the first entailed not leaving her room for days, while the other was of hunger. Before she finally left to study sign language in Jordan, as there were no such institutions to teach it in Palestine, let alone a Palestinian sign language, she informed her father that she would take off her headscarf there, and she would return home without it. Upon finishing the course, Almaza rushed back to Jerusalem, to show her father that she actually followed through on her promise. When her father saw her, he walked away, refusing to greet or speak to her. But on the following day, he suddenly invited her to join him to visit the wider family, walking with her proudly.

With her sign language certificate, Almaza, alongside G. and other leftists, started work on creating a school for deaf Palestinian children. It was during this endeavour that she also started working on the first Palestinian sign language dictionary. She would, however, leave the group; they wanted her to become a teacher at this school, while she demanded the hiring of qualified teachers, not someone who hardly completed the eighth grade. Still, she suggested teaching these teachers sign language. Her insistence and unyielding position on the matter meant clashing with the other feminists and leftists in the group, including G., who all accused her of being pedantic. The sign language dictionary was completed and published, but the work that she did, including her comparisons with Egyptian, Jordanian, and Israeli sign languages, and meeting its practitioners to invent a Palestinian sign language, are recognised in the dictionary in the form of a special thanks, for her patience, and nothing more.

Disillusioned with this group and how they came to be more concerned with power than the realities of social life, she returned to typing and took work as a typesetter in a major Palestinian newspaper, as well as typing scripts on behalf of Palestinian playwrights. Almaza eventually worked in a Palestinian theatre only to be reminded, repeatedly, by the management that she had never finished secondary school, to stave off her protests against her meagre salary. But by then she had managed to buy an old, small car, allowing her to see her kids more often and drive around with them; her dream. At the same time, she pursued a two year diploma in office management, after convincing the college to accept her despite not having finished school.

When she graduated, Almaza was thirty years old. At that stage, she decided she wanted to leave everything behind and start a new life in a new city. It was Rome. A friend there, whom she knew from the women’s union, told her of a vacancy for a typist and proof-reader of an Arabic magazine to be launched by a Libyan media company. Almaza was hired but found the job dull, and asked her friend to help her, again, in finding another. She received an offer to be an editing assistant at an Arabic TV station broadcasting from Italy, but it was around this time that, as Almaza was preparing to update her immigration status with this new work contract, her bag got stolen with her Jordanian passport and Israeli travel document and ID. Almaza remembers the bemused Italian police when she reported the theft, with her place of birth: Palestine; passport: Jordanian, travel document and identity card: Israeli. After two months of torturous humiliation accompanying her visits to the Israeli embassy in Rome, she was given a travel document valid for one month, and ordered to return to Palestine and renew her papers in Jerusalem. Back in Jerusalem, back as a secretary in the theatre, back as a receptionist for a Non Governmental Organisation that brought Palestinian businesswomen and female workers under one umbrella, back crossing the checkpoints, back to work in Jerusalem’s old city with a cultural organisation. After this last job, unable to stand the methods of the Israeli occupation in the Old City, Almaza went back to Ramallah, where she landed what she considered the job she loved most: a receptionist at a mobile phone company.

What now? I ask. Enjoying her time off, she says, the first break from the blender that she felt her life had been thrown into for the last four decades. Now I’m just on the edge of the blender, not in its heart. Unemployment brought stillness to a mad life.

Why on the edge and not completely out? I ask. Because we are still in Silwan, she replies, surrounded by settlers who push us increasingly out of their way and against each other. There was a small piece of land, she explains, where kids used to play. The settlers seized it, put up a high fence and turned it into a basketball court with a gate which only opened for their children.

The neighbourhood kids now play in the small alleyway in front of our house. Their screaming and shouting all day drives us mad, gives me immense headaches. They are just in front of our door all the time. So, every day you are faced with the settlers and the Israeli sense of superiority, where you are made to understand that you, as a Palestinian, deserve nothing, not even a spot for your children to play, or a parking lot for your car, a proper road to cross.

Almaza catches herself, and lifts the tone of defeat that momentarily seeps into the air. But we’ll always find new ways to continue. We have to. One needs to keep rejecting the conventional solutions offered to them, to the many of us.

Almaza continues to crochet; the pieces she’s producing now are a record of how long she’s gone without work.

Almaza is 56. She was born during the 1967 war at home, during curfew.