The proceedings have had a breathless, frenetic infancy. South Africa’s case contends that Israel has violated its obligations to prevent and punish the commission of genocide during its accelerated invasion of Gaza following Hamas’ attack on Israeli territory on “October 7.”1 It brings its case not as a specially affected state, but as a party to the Genocide Convention seeking to enforce that treaty’s obligations against another party. South Africa’s standing to do so would have once been doubted; though it is now uncontroversial that this course is available under international law.2 On 26 January 2024, the Court ordered “provisional measures” of narrower compass than South Africa had sought,3 requiring Israel to ensure its ongoing compliance with its obligations under the Genocide Convention, and to enable the provision of urgent humanitarian assistance to Palestinians in Gaza.4 The Court did not order a ceasefire. South Africa twice sought further provisional measures, with the Court acceding in part on 28 March 2024. Again no ceasefire was ordered, although seven of the sixteen judges opined that they would have supported such an order.

Legal analyses of the Court’s decision are abundant.5 They sit on the spectrum from technical and purportedly value-neutral outputs of legal formalism, to more honest efforts at teleological appraisal. To a student of critical legal theory, one can only sensibly judge the proceeding by reference to its capacity to advance its (supposedly)6 anti-colonial purpose. That purpose can be pitched at differing levels of generality. It is, in its most fundamental modality, the free and unfettered exercise of Palestinian self-determination. But to realise that purpose presupposes that certain material conditions will come into existence: an end to Israeli occupation, the reversal of settlement activity, emancipation of Palestine’s natural resources, formalisation of Palestinian borders (and not under the regressive “Bantustan” conditions of the Oslo Accords)7, governmental independence. In turn, this demands that Israel relinquish its daily genocidal toolkit: targeted killings, arbitrary detention, torture, indiscriminate bombing, starvation.

Against this background, we can draw three observations about the possible fate and significance of the proceedings in delivering Palestinian self-determination. The first is that even a favourable outcome to the proceeding will scarcely assist to achieve an end to genocide in Gaza. The likely passage of years until any resolution on the merits will dilute the practical force of a finding of genocide. By then, Israel will have taken up other strategies for depredation and annexation, which will invite their own legal scrutiny and further belated judicial rulings down the line.

To know this, we need only look backwards. Most of the material conditions of Israeli settler colonialism have been tested before international courts at some point. Every available (legal) avenue has been pursued. In 2004, the ICJ gave an ‘advisory’ opinion (upon request by the UN General Assembly) that Israel’s construction of a security fence in the West Bank and East Jerusalem and its attempts to alter the demographic composition of Palestine violated international humanitarian law (“IHL”) norms governing occupation, Palestine’s right to self-determination,8 and various protections under international human rights law.9 The Court, too, observed that Israel could not rely on its right to self-defence to justify construction of the wall;10 and that its construction created a fait accompli on the ground that was tantamount to de facto annexation.11 The Court ordered, inter alia, that construction cease and that the wall be dismantled. Israel did not comply and continues to pursue its settlement activities with impunity.

In 2021, the International Criminal Court (“ICC”) decided, after six years of preliminary examination, to commence an investigation into war crimes committed by individuals in Palestine since 13 June 2014. This followed a determination that the Court had jurisdiction to do so, on the basis that Palestine was a “State” for the purposes of the Court’s founding treaty, the Rome Statute.12 But the Court could not—and did not—determine whether Palestine was a State for all purposes under international law.13 It acknowledged the ICJ’s 2004 advisory opinion and endorsed its conclusions in some respects (including Palestine’s entitlement to self-determination).14 Investigation will take the best part of a decade;15 fact-finding will be enormously difficult amid Israel’s monopoly on access to Palestine and certain non-cooperation; and the Court will likely be unable to execute an arrest warrant on any Israeli who is ultimately charged.

There are pending proceedings, too. There is an inter-state complaint by Palestine against Israel to the Committee administering the Convention for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, alleging a violation of the prohibition on apartheid.16 Palestine brought an ICJ proceeding against the United States in 2018, alleging that the relocation of their embassy in Israel to Jerusalem violated treaty obligations governing consular relations. No decision on jurisdiction has yet been made. Countless fact-finding missions by human rights bodies have also presented evidence of Israel’s grave and persistent breaches of IHL and human rights law in the Palestinian territories since 2000.17 Finally, in December 2022, the UN General Assembly submitted a request for an advisory opinion on the consequences of various Israeli “policies [and] practices”18 in Palestinian territory under IHL, human rights law, the UN Charter (including the prohibition on the use of force), General Assembly and Security Council resolutions, and the Court’s 2004 advisory opinion.19 The scope of this proceeding may appear the broadest so far, but the Court has at times been inclined to reformulate and narrow such open-ended questions.20 At any rate no opinion is imminent, and when it does arrive Israel’s “policies and practices” will have likely accelerated and morphed.

Seen in this light, the South Africa proceeding is but a node in a fragmented litigation strategy—what is sometimes odiously described as ‘lawfare.’ By its nature, a court’s jurisdiction is limited to resolving the dispute before it. As framed, South Africa’s claim alleges breaches of the prohibition against genocide. It does not reagitate Israel’s obligations under IHL, including to avoid indiscriminate loss of civilian life. It does not consider the criminal liability of Israeli officials for the commission of war crimes or crimes against humanity, nor Israel’s state responsibility for authorising that conduct. Nor does it, in express terms, call for inquiry into ongoing violations of the Palestinian right to self-determination or statehood. These issues have been or will be ventilated to certain extents in separate proceedings.

This flows onto a second observation. Against this history of litigation, one aspect to South Africa’s proceeding is truly unprecedented: the claim of genocide. One tool from which Israel draws discursive power is its emotive manipulation of international legal concepts. The Holocaust, being an “intense national preoccupation” and the “basis for Israel’s identity,”21 renders genocide the concept most susceptible to manipulation. Zionism attributes the enactment of the Genocide Convention to a singular desire to avoid any repeating of the Holocaust—only a partial truth as Raphael Lemkin, the moving force behind the Convention and inventor of the word ‘genocide,’ had in mind other genocides too.22 Zionism positions the Holocaust as the “paradigmatic example” of genocide,23 against which any later allegation falls to be assessed and which Zionism says Palestine wishes to reprise. By this exploitation of the Holocaust, which Pankaj Mishra traces back to the former Israeli Prime Minister, Menachem Begin,24 Zionism can operate in what Boaz Evron described as a state of complete freedom from “any moral restrictions, since one who is in danger of annihilation sees himself exempted from any moral considerations which might restrict his efforts to save himself.”25

The separate opinion of Judge ad hoc Barak, Israel’s appointee to South Africa’s proceeding—dissenting, naturally—is replete with textbook narrative manipulation of this kind. Before deigning to consider the provisional measures application before the Court, Barak gratuitously relates his own Holocaust experience,26 the relevance of which, he says, is that genocide is “more than just a word” to him; it is “deeply intertwined with [his] personal life experience.”27 This makes him “deeply aware of the importance of the existence of the State of Israel.”28 Later, he suggests that applying the Genocide Convention to Israel’s conduct in Gaza would “dilute the concept of genocide.”29

If genocide were to be established, one suspects the only ‘dilution’ would be to the potency of Israel’s claims as its worldwide scrutineer. To hold Israel against the very concept it most jealously gatekeeps involves a daring feat of legal imagination. A ruling of genocide—the “crime of crimes”30—would shatter Israel’s moral hold over the concept. There would be a mighty symbolic force in that result, an “epoch-making event”31 by which international law can show that in matters of ‘high politics’ it does not yield to power or selective patronage. In that event, moral cowardice might lead Zionists to reassert their hold over the concept and discredit the Court’s handling of it (an option for which Judge Barak appears to be laying the foundations from within).32 That appears the more natural response for a political ideology premised on a persecution complex. Our hope must be that the refraction of the moral weight of genocide back onto Israel causes a volte-face of the kind we have never seen in nearly 80 years—one familiar word that brings on a prick of conscience, and a coming to terms with its own barbarity. Then they may realise that genocide is “more than just a word” to the Palestinian, too.

This brings me to my final observation, as to the clash of narratives beneath it all. Zionism has long been able to outwardly project its self-image with monolithic coherence. As Dylan Saba observes, Zionism has mastered the “language of minoritized grievance” so that its exercises of State power, however excessive, are to be understood as against its “transhistorical” narrative of anti-Semitism.33 In turn, international law has reified this narrative, conferring on Israel the legal incidents of statehood and the corresponding advantages of incumbency. And so, in one breath, Israel can invoke the customary right to self-defence and deny its availability to any Palestinian entity. Where the decolonial animus within international legal scholarship holds the law against Israel, it then resorts to emotive manipulation of the kind which, for instance, leads it to describe South Africa’s proceeding as “blood libel.”34

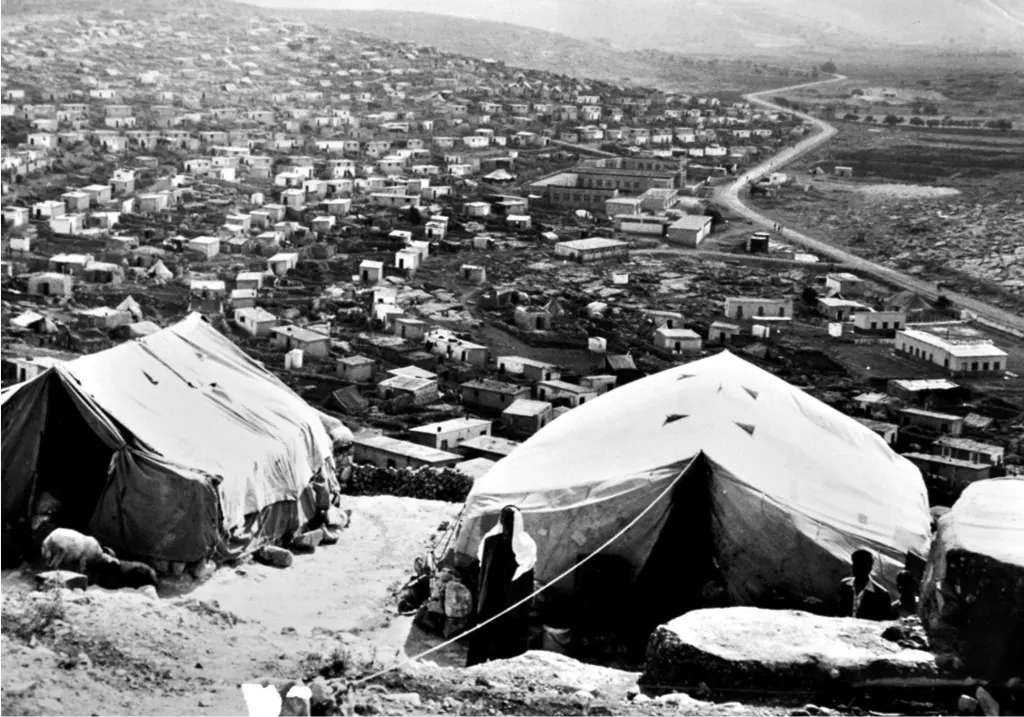

The Zionist hold over history draws greater strength, still, from Israel’s ongoing campaign to fragment every aspect of the Palestinian experience: their territories, families, possessions, infrastructure, and daily lives. Physical, cultural, and historical fragmentation has been a technique repeatedly used in the pursuit of the Zionist goal to annex and eradicate Palestine.

How, then, does the current proceeding fit in?

On the one hand, it bears contemplating whether the proceeding in its present form and scope invites further fragmentation of the Palestinian narrative. Because the incumbent territorial and political arrangements from which Israel benefits have been enshrined and legitimised by law, they can only be unwound with a countervailing force of law. After all, law supplies the analytical vocabulary we use to make sense of the dispute—rights, genocide, apartheid, self-determination, self-defence—and ascribes or withdraws political and moral legitimacy.

However, South Africa’s case can only legally proceed on a temporally and experientially miniscule fragment of the Palestinian story: the commission of genocide, one particular legal concept, over a finite period of time from late 2023. Other parts of the Palestinian story can only be presented insofar as they are relevant to the precise fragment under the microscope.

Further, that fragment is being conveyed through an intermediary state. This is a forensically apt arrangement, which circumvents any complaint about Palestine’s non-statehood; but it surely carries some symbolic cost to Palestine’s agency and its burgeoning attempts to participate as a state in international fora. The very same limitations constrain each past or pending piece of international litigation. One wonders, then, how we can unwind a state of affairs ossified over 80 years by procuring rulings which do not question, and indeed perpetuate, the generative injustices which lie beneath—the Balfour Declaration, the end to the British mandate, the Nakba?35 Are the cases not litigating the expressions of Zionism and not their source?

This is a continuing challenge for the Palestinian political program. But there is reason to hope that, perhaps, the cumulative effect of this strategy will be to eventually uproot the Zionist narrative and produce some change to material conditions.

Recourse to a fragmented litigation strategy is not optimal. But the number of judicial determinations confirming the illegality of Israeli settler colonialism so far obtained is a product of great imagination in the face of suffocating constraints. And it is slowly compiling an ever-clearer, deeper and transhistorical picture of Israeli brutality. In that respect, the pending ICJ advisory opinion on Israeli “policies and practices” offers the best hope for the sort of comprehensive legal adjudication that so far has eluded our grasp—one which goes back to 1948 and parses each step, each grievance. Perhaps with the benefit of that fragment, and of this one which speaks of genocide, no longer can Israel hide behind its “long-cultivated persecution mania.”36

As Mishra observes:37

All these universalist reference points – the Shoah [Holocaust] as the measure of all crimes, antisemitism as the most lethal form of bigotry – are in danger of disappearing as the Israeli military massacres and starves Palestinians, razes their homes, schools, hospitals, mosques, churches, bombs them into smaller and smaller encampments…

And so, Sisyphean as it may seem, there is something to be gained from this exercise. We will continue to prise open the Court’s maw, and take from it whatever fragments we can. And from those fragments to which Israel reduces us, we will piece together our own narrative, and “turn the whole hegemonic picture upside down.”38