1.

Tarn Street is where we would go if we wanted to get out of it all. Yes, this is where we would go. Once a long street full of life, it’s been chopped down to a mere 30 metres. Nevertheless, this remnant is a refuge if you want it. Yes, Tarn Street in The Elephant & Castle, that nebulous neighbourhood in Southwark, South London. Nearby, the Heygate Estate was 1100 public housing flats which have been demolished to provide some petty manifest destiny for the upmarket Elephant Park development. So, our muscled memory walk from The Heygate was always along New Kent Road, down Meadow Row, past the Rockingham Anomaly—London’s only patch of subterranean peat, a 300 metre wide circular depression in the landscape, our lucky charm curiosity—and then you’re there. Tarn Street. We’ll get back to it, but first…

We pass these newly built ruins that sting our eyes: here indeed be “Regeneration.” That word! Those imprecise words they love—“progress,” “regeneration,” “reinvigorating,” “transforming,” “revitalisation.” We’re fucked when those words come out to play. This Tarn Street, this Elephant, this Southwark, England, the U.K.—overseas investors, financial vehicles, sovereign wealth funds from Qatar, Canadian, and Dutch civil servants’ pension funds and offshore capital land right here, all as part of the intercity, inter-regional and global competition to attract serious money to lay waste. These civilised servants of the state favour growth and profit, love the damned GDP and believe in the fiction of The Economy with its one-trick-pony reliance on new housing as the answer to recession and crisis.

Here in Southwark, Tony Blair’s years of New Labour governance and planning were ridden wild by the Council in a demented Centrist rodeo, resulting in a total disaster for local people over the last decades. Blair’s first speech on winning power in 1997 was made nearby, on some steps at the Aylesbury Estate. We needed to “refashion our institutions to bring this new workless class back into society,” he said, locating the council estate as the locus of feckless work-shy Britain. What could they aspire to, these scum of the Earth? Should they believe in the myth of a meritocracy where hard work, good personal management, aspirational and middle class values of individualism and property ownership in all its forms (material as assets, relational as status, interpersonal as a weapon) would magically remove basic structural disadvantages for anyone now shameless enough to remain poor?

This civic determinism was spearheaded by Peter John O.B.E, Leader of Southwark Council from 2010 to 2020. Although a dull probate lawyer by day, by night Peter John had dreams to Get Things Done and so rushed into a deal with the developers, Lendlease, to knock down The Heygate as the first part of ‘rebalancing’ the area. The Elephant Shopping Centre would be knocked down later. He was determined to “deliver progress.” Demolish public housing. Demolish space to shop and socialise cheaply. A trail of stigma and manufactured ignorance about the lives of working-class people was heaped upon Heygate tenants. “Regeneration” needed to produce its own accompanying poetries of hate:

“…is this the Third World or what?… sink estate, plagued by crime drugs and prostitution, violence and deprivation… if you give people sties to live in, they will live like pigs… apocalyptic movie, hooded teenagers, dogs, mothers pushing prams, crime-racked labyrinth of grey high-rise, doomed behemoth, failed utopia, mugger’s paradise, meths-drinking weirdos… sorry but it looks shocking.”

Peter John said that “the way to solve a housing crisis is to build new homes” and so, in a massive act of state-led social cleansing, from 2014 onwards, 3000+ mostly private homes came to pass on the ruins of the Heygate. The Council—a double helix of ignorance and ideology, petty corruption and stupidity—tried to convince locals they were doing something progressive; but all promises made to Heygate tenants were relentlessly broken, and they were dispersed far and wide across the borough. “Regeneration” is much more complicated than simply the rich trampling the poor; “gentrification” is a redundant description of complex processes of community destruction in the always uneven, classed, and raced economies of inner city living. Ain’t no Black in Elephant Park—just delis!

Perhaps, in his apartment in fancy Shad Thames, Peter John looked into his mirror in 2015, sized himself up and extrapolated from his pale reflection that he was the future Southwark. “Regeneration” is fashioned in its own image: those who deliver it can only imagine themselves as the archetypes for the desired demographic switch. Later, Peter John was able to polish his Order of the British Empire—awarded for his political services—before stepping down from council life to hang out with those consultants who were the PR people for Pinochet.

But the bourgeoisie has always known that kind of bad faith inside out. It produces and enjoys its own theatrical spectacle. It is the class most founded on image, on showing itself (off). It enjoys front row seats to the spectacle but never knows whether to keep looking at the stage or to watch out for trouble. Everything predicated on the Good Life and nothing for anyone else. Not one of them is innocent. They really believe in the poetries of the developer’s brochures:

“…Discover your next chapter, imaginative designs, luxury finishes, inspirational locations and cutting-edge architecture, curating your life, so you’re always surrounded by the things and people you love, living well is a way of being, communal gym, elevated garden, fast WiFi, sky lounge to enjoy the views of London, 24-hour concierge service, located in vibrant, thriving communities, meaningful environments that contribute to your wellbeing, curating your space, it is an ability to make a positive difference in your own life…”1

2.

So we found ourselves in shitty Tarn Street once more because we wanted to study those dense layers of progress with their own possessed imagery. A bunch of us took a playful walk on 10 April 2024 and talked about “The Encounter,” where one way of living, with all its discontents, meets modes of supposed modernity, which are then experienced as great waves that violently sweep away how you have lived and how you have grown together in that living. Here come new things, new people, new phantasmagorias; always with contempt for what they have displaced. We read aloud from Chapter 31 of Abdelrahman Munif’s Cities of Salt (1984) which describes a meeting of this kind: desert communities of a fictionalised Saudi Arabia encounter the arrival of the American oil companies which rewrite their fates under a new regime of petrocapitalism. Tarn Street—a place astoundingly heavy with The Weight of Progress embedded within its material structures, dead labour, and the spectres and spooks of proletarian longing which still seep from the terrain. Malodorous intent. What can be found in this fragment?

Overhead, the railway bridge dominates, those trains so loud, interrupting our reading of Munif. Those vast stone pillars, the iron ribs of the bridge, the dense brick work. The expansion of this railway line from The Elephant to the new Blackfriars happened in 1860, 20 years after Railway Mania and unregulated laissez-faire expansion—the hidden hand here, the chopped-off hands there. Smack bang in the years of empire those train lines displaced the locals in some of the first clearances of poor people in London; no compensation, no rights, just eviction.

Five years later Francis Galton’s article Hereditary Talent and Character kickstarted the English eugenics movement. Who can put their hand up and say they don’t see a parallel between social cleansing and Galton’s breakdown of populations into Desirables, Passables and Undesirables? Heygate tenants were infamously described by Council officials as the “wrong sort of people” and seen as a surplus population who still had the cheek to live in the area. An “undeserving poor” reimagined for the social sadism of the 21st century. The opposite of regeneration is degeneration and eugenicists had a fear of regression. At the Elephant, us scum have been called upon to ‘improve’ ourselves because the deranged, the disturbed, the disabled, the disadvantaged have all become suspect, a problem that needs ‘solving.’

Another train pounds above us, time is skewed; steam, whistles and sparks and soot. The English romance of the smoky passenger train masks the colonial technologies that allowed the new steam boats to reach the colonies, and allowed those extracted and looted raw materials and commodities to be exported via new railway lines. Such trains were the vanguard of British “civilising” missions. Here at Tarn Street was a large coal depot for black fossil fuel to be burnt in locomotive fireboxes. Through this black miasma we see behind us the lovely 1930s London County Council public housing (with promises of inside toilets) where blocks are named Telford, Stephenson, Rumford, Rennie, Rankine after the gentlemen engineers of the industrial revolution. Their contribution to infrastructure: roads, canals, iron bridges, railways, docks, warehouses, stream engines, shipping. The combined power of mechanisation and capital. No modernity without industrial revolution. No industrial revolution without empire.

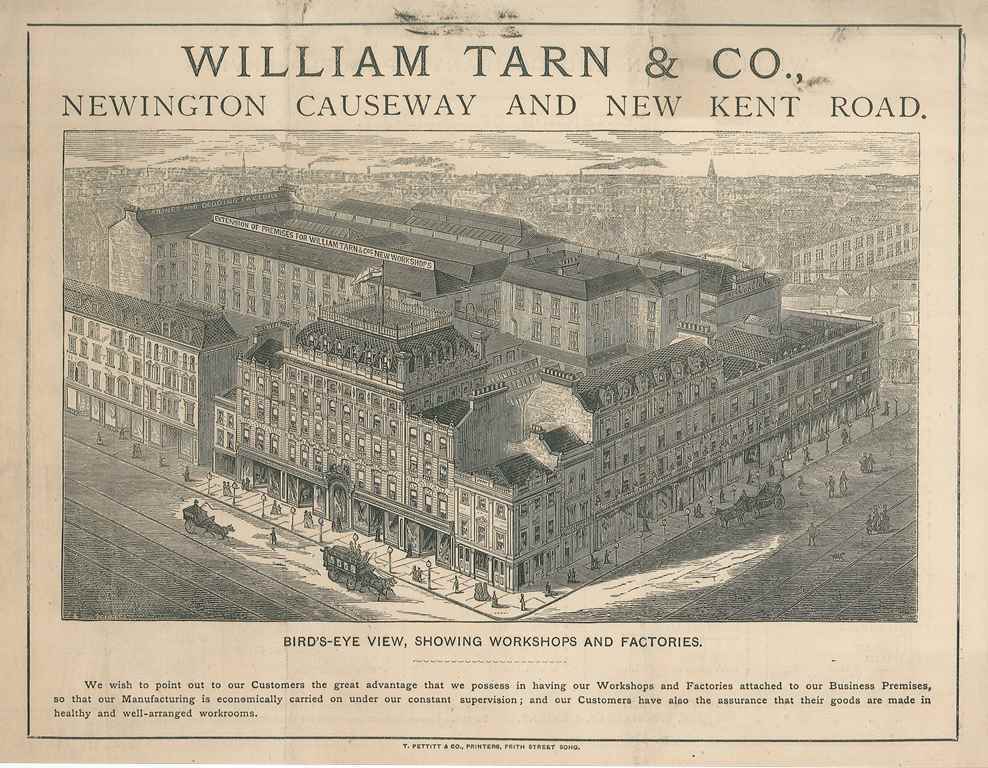

So, from this Wealth of Nations, our Tarn Street got its name. Nearby, Tarn’s Department Store expanded decade by decade to cover a whole block from here to New Kent Road by the 1890s. This department store, so beautifully painted and deconstructed in Emile Zola’s The Ladies’ Paradise (1883), with so much Victorian pride in its own commerce, entices us inside. So many things in a world of having. Behind the scene’s gendered labour, petty management catered to the whims of the bourgeoisie. Tarn’s left a beautiful archival paper trail of illustrated brochures, catalogues, leaflets, advertisements, price lists, dockets, invoices, documents, receipts and so on where in essence they reproduced images of themselves in their own poetry of having stuff:

“…silks, velveteens, ribbons, furs, lace, french merinos, cachemires, damasks, wool brooches, english serges, pompadours, sideboards, dining tables, walnut chairs, overmantels, mahogany bookcase, couch, settee, bamboo screen, gents easy chair, ebonized pedestal, newest colours—eucalyptus, serpent, lizard, goblin…”2

Just back from the railway arch is the HQ of the Salvation Army, the evangelical Protestant sect and serious conniver with British imperialism. Established in 1865 the Army wanted to guide the “submerged tenth out of the jungle of Darkest England” but only through a philanthropy with ropes attached. Their idea was a process of “regeneration:” gathering up the outcast poor via calculated “invasions” of godless communities bringing food, shelter and, of course, work. Essentially the same justification as the regressive stigma foisted more recently on us heathen locals. The crucible of material conditions that produce any “anti-social behaviour” can be prayed away and solved by appeals to be a better Spirit, rather than being brought out of poverty by a society that cares for all. Enter a regenerated Empire of Souls. Anyhow, the Salvation Army have now flogged off their building for £45 million to developers for a scheme premised upon “local people directly benefiting” and being a “community-oriented scheme,” yet it is actually a 425 room hotel and 25 storeys of offices.4 Hallelujah!

Outside, here in this street, in this constellation of histories and aggressions, where wealth did not abolish poverty, we continue to loiter on this carpet of bones and slime. Richer folks new to the area walk across, never slipping, but never quite getting their feet free of the adhesive pulp of proletarian lives.

3.

So, we feel that Tarn Street exists for those who want to get out; for those who don’t want stuff and who aren’t nostalgic. For those who wish to remain irrational. So, here we are, here and now, at Tarn Street where there’s nowhere left to run. But why is there nowhere left to run? Because of Tarn Street and what it means to you. Loner. Runner. Loser. Tarn Street is our chosen ground. Spin around and all the blood in your mind and body reads the landscape clearly and correctly. Centripetal imaginations are powerful on this archipelago of unease: old stores, old people, dead and buried, the long gone Columbian restaurant Leños & Carbón (literally Logs & Coal), the nearby Hand in Hand pub and Eileen House; anti-gentrification bases which were squatted before demolition, strangers feeding the pigeons, and that bricked-up door to nowhere in the railway arch which always felt like it could be a way out.

The base materialism of their progress is our decay. But it cannot last and it cannot hold: our resistance is everywhere and the poetries that we have produced are lived and not in words.

Katie Lake, draper’s assistant in Tarn’s in the 1870s, later admitted to Newington Workhouse where she died from tuberculosis.

The owner of the coffee stall on Tarn Street in the 1950s, cursing his midnight customers, both good and bad.

Maisie, an affable sex worker, who was Bert Hardy’s local guide to the area for his post-war photo portrait of The Elephant in Picture Post, 8 January 1949.

Ebele, the Nigerian woman who came to the now demolished Palace Bingo two or three times a week for community.

Our lecturer friend at her University—itself a development partner in the “regeneration”— disciplined by management for speaking out against their complicity in social cleansing.

Emad, the Egyptian who ran his computer shop in the Shopping Centre and learned Spanish to help the local Colombian community, who was forced out of his business by the “regeneration.”

Janet, who bought her wedding dress in the Shopping Centre 45 years ago, but now roams the area in her mobility scooter without her daily trip to Jenny’s Cafe. She speaks of the Centre as “a beautiful love affair which will never die.”

The Polish Nanny, the Filipino Cleaner, the Brazilian Deliveroo rider, the Afghani phone repairer, the Albanian chef, the English student charity mugger signing you up for some more “we are all in this together”—and everyone else still standing.

So, here we all are. Here we are at Tarn Street, huddling in our fragment. It’s ok, maybe. The mountains of the Elephant & Castle have moved. An Elephant, you say? A Castle, you said? Our escape is a political-poetic act or the other way around! Or, us placing a hand on the brickwork, the metal pillar, the grimy pavement or the billboard soaked in black tar, our faces reflected in that dark mirror and we feel our soft flesh and blood start to corrode these poor histories. We were always the anomaly! We are the remaining fragment, too. It’s The End but we aren’t yet dead.