Act I.

Classical music’s self-diagnosis as a “heritage” art form1 coincided with its dwindling participation and interest from the wider and global public in the 1950s. Since then, maintaining the relevance of classical music to a more contemporary and multicultural audience has been challenging. With the average age of an attending audience member being in their late 60s to early 70s, a typical response by opera companies has been to increase reliance on government funding and gradually raise ticket prices.

Once a year, Australia’s largest performing arts company, Opera Australia, announces its upcoming season. The annual highlights consist of the Handa Opera on Sydney Harbour and its mainstage series program. The focus of the company has become increasingly narrow, conservative, repetitive, and dare I say, Verdi-oriented. Rather than expanding its horizons to become a more sustainable cultural institution, the company has appeared to double-down on its mission to present opera in its “golden age,” perpetuating the notion that operatic theatre is a place for nostalgic spectacle. Is the claim of “heritage” an excuse to continue staging problematic spectacles in the name of classical tradition, or is it the only viable manner to save this—self-admittedly—dying classical art form?2

I have wavered between opera’s traditionalism as a response to economic realism or viewing it as complacent creative direction and have fallen towards the latter. Although I acknowledge that components of heritage and tradition exist in all art, I have learned that Opera Australia represents a space that actively excludes the new, the young, and the so-called ‘Other’.

Act II.

“Examine this boat all over, and see if you find any leaks. I can see them. And what am I to do? The world is expecting an opera from me, and it is high time it were ready. We’ve had enough now of Bohème, Butterfly, and Co.! Even I am sick of them!”

Letter by Puccini to Tito Ricordi

New York, February 18, 19073

Opera Australia perceives their art form as nothing more than a rotating ethnic degustation menu cycling between their three most performed opera composers: Puccini, Verdi and Mozart. The company’s opulent presentation of “popular” opera does little to inspire the imagination, and to borrow from music critic Nancy Groves, leaves no rhinestone unturned.4 Relying on a programme where fantastical displays of culture do little else but Orientalise suggests that Opera Australia and its demographic are dependent upon these worn-out productions that use Oriental culture for the sole purpose of nostalgic spectacle.5 It should be noted that there are other non-exoticised options—for example in 2021 they are staging Bluebeard’s Castle by Bartok. This token work aside, the rest of 2021 consists of staples of the operatic catalogue all composed before the year of 1912; Puccini twice, Offenbach and a whooping four works by Verdi!6 Simply gazing at the choices of Opera Australia’s mainstage, it is difficult not to consider these repeated choices a musical safari masquerading as fine art. These are works of their time, with the 2021 season presenting operas spanning 1844 to 1911, but why must their performance and production be performed in a manner that can only be described as archaeological?3

By archaeology, I refer to Opera Australia’s presentation of the entire art form as artefact and archive. Archaeology, in its most basic form, is the blending of humanities and science to study human history through material culture. In this sense, Opera Australia’s reinvigoration of a living form of performance art appears to rely predominantly upon the music of the dead. However, artefacts and archive are novel curiosities: when performed, they hold little relevance to a space that cannot deny the contemporary perspective of its living audience. Unlike the disciplines of archaeology and heritage, the performing arts are not centred upon the study of the past. Opera is not simply an act which can be archived, never to have its inherited cultural value questioned or interrogated. The interpretation of opera as a form of cultural heritage is a continually evolving process in which ideas are expressed and stories are told.

In other words, opera is a living practice that depends upon performers and performance to bring it to life. What a shame that so many of the living are required to rehash what those who have passed might have seen two hundred years ago! The novelty of such an archaeological performance begins to wear thin. Insisting upon anachronistic approaches such as brownface (as I will analyse below) makes these forms of opera indifferent to the nuanced realities of contemporary life, thus reinforcing arrogant and racist hierarchies where the white gaze remains in a position of authority.

In 2016, the National Opera Review published the following statement and series of recommendations regarding the artistic vibrancy of Australian opera companies:

“Opera Australia and Opera Queensland, in particular… [reduced] the number of mainstage productions and/or performances they offer and, in the case of Opera Australia [offer] longer runs of frequently repeated popular mainstage operas. The unintended consequence has been that audience numbers for mainstage opera have declined and employment opportunities for artists have significantly decreased. The Review considers that such a situation is not sustainable.

…

Other initiatives are required to increase artistic vibrancy, including supporting the development of new Australian works; presenting works in association with festivals; and increasing the use of digital technology… Such recommendations would also support increased employment opportunities for artists.”7

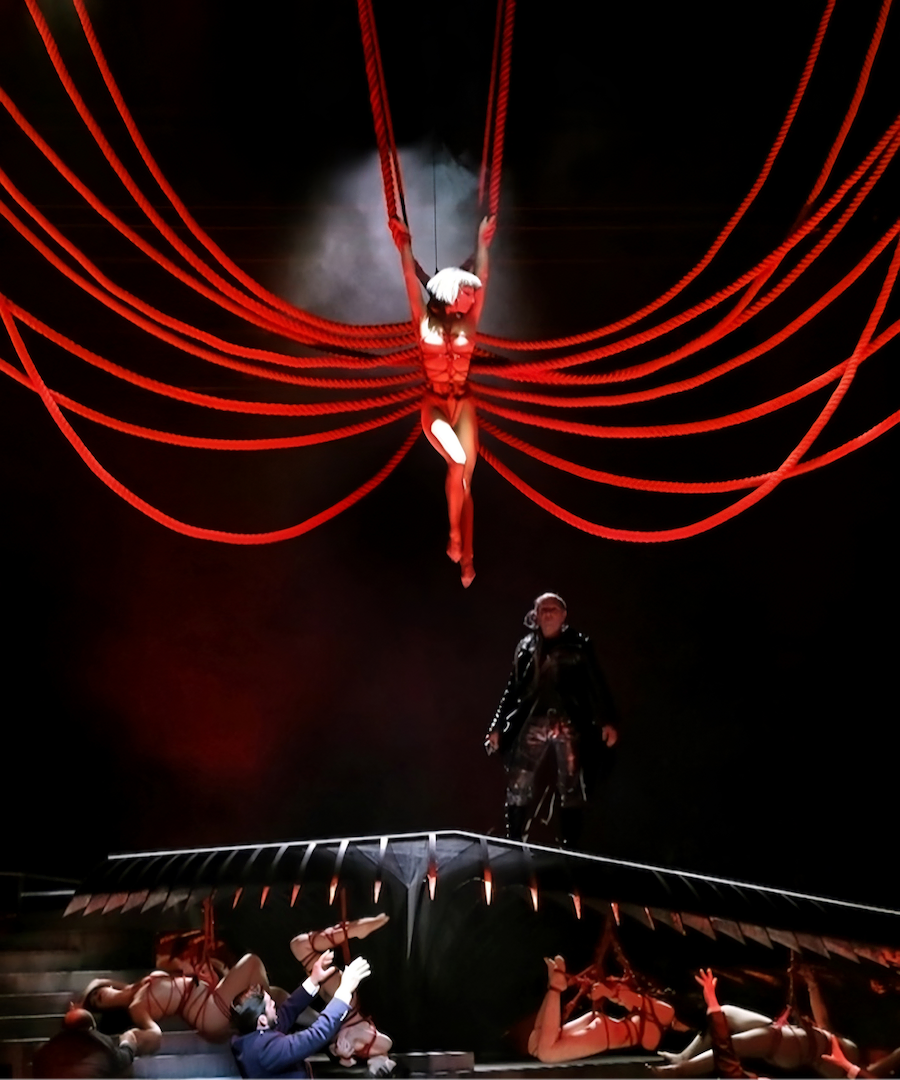

One could argue that the integration of digital technologies in Opera Australia’s presentations is an admirable response to the Review’s recommendations, most notably in their restaging of Madama Butterfly in 2019 and Aida in 2019-21. Although these performances can be commended for their visual delivery, their grandiose presentations do not mask the heart of the issue. A clear case study would be the 2019 production of Madama Butterfly directed by Graeme Murphy, as shown in the image below.

In Madama Butterfly, Puccini’s main character Cio-Cio san is frequently referred to as Opera’s most hysterical mother. In Murphy’s restaging, rather than interrogate the sexist overtones of hysteria bestowed upon Cio-Cio San and the racist characterisation of Japanese women as overtly feminised and fragile, his production chose to reinforce tired, patriarchal stereotypes. In particular, the stage design sought to enhance these fantastical tropes of sexual exoticism in the name of ‘authenticity’. The integration of 10-LED screens into the stage design was lauded as a “so much going on visually,”8 yet, it is nothing more than a backdrop to the problematic representation of the characters themselves. It is difficult to see beyond the bondage-themed presentation of Cio-Cio San and the sexualised fantasy that is depicted around Japanese culture, given that Murphy’s Madama Butterfly exaggerates an already fetishised image of Japanese women through his integration of kawaii girls and Japanese bondage. This panders to the obsession of the Western gaze and its objectification of Asian women, here, quite literally strung up like marionettes to be played and toyed with for sexual gratification.

The only thing authentic about this repulsive simulation of Asian women is that such Orientalist characterisations continue to negatively affect those lives. Perhaps Murphy’s justification for this shallow representation of ‘The East’ is that the production was an effort to pay respects to Puccini’s Butterfly, and to garner a wide audience to support such an expense; sex sells. Operas such as Murphy’s, in their obstinate belief of ‘authenticity,’ perpetuate a deliberate misrepresentation of non-white cultures and people of colour. Opera Australia’s claim of modernisation through incorporating digital media does not alter the core of the performance nor its unsavoury presentation: technology is but a thin veneer for its enhancement and reprisal.

Similar to Murphy’s Madama Butterfly, Opera Australia’s upcoming production of Verdi’s Aida also relies upon projection and digital media. Like the 2019 Butterfly’s insistence upon exaggerating a sexualised caricature of Asian women, the trailer for upcoming Aida expresses nothing but a cheap depiction of Egyptian culture that trades in antiquated tropes of half-naked women, gaudy gold costumes and ceiling-high walls adorned by hieroglyphics. Technology does not reduce the problematic spectacle that the company has chosen to rely upon, thus driving home a key point: using modern technology does not in and of itself modernise the presentation of your subjects.

The form of authenticity that Opera Australia believes in is fundamentally flawed: their productions are not ‘authentic’ in the sense of an actual historical or contemporary reality. Rather, they are only ‘authentic’ to the extent that they habitually reinforce a racialised Orient from and for an anachronistic Western perspective. This so-called ‘authentic theatre’ is little more than a shallow impression of other cultures that the 21st century has long since understood as racist. More directly, Opera Australia’s interpretation of the ‘genuine Orient’ is measured by racist conceptions of authenticity.

Opera Australia’s 2015 production of Aida encapsulates the consequences of this misplaced desire for an ‘authentic’ spectacle at the expense of people of colour and their dignity. The dreadlocks and brownface in which Australian baritone Michael Honeyman performs in is a cumulative result of artistic direction, costume, and makeup. Perhaps Opera Australia’s aim was to preserve a sense of mystical exoticism in the name of heritage. Or perhaps it was a misplaced effort to honour the original desires of the Viceroy of Egypt, outlined in the following excerpt from 1870:

“The Viceroy wants the opera to retain its strictly Egyptian colour, not only in the libretto but in the costumes and the sets… Add to this the exotic quality of the mise-en-scène…To create imaginary Egyptians as they are usually seen in the theatre is not difficult…”9

We no longer require the conjuring of imaginary Egyptians or “Oriental Peoples”10 as they are “usually seen in theatre” as the West may have in 1870. More than 150 years later, opera need not rely on such outdated modes of presentation. This archaic reimagining of Ancient Egypt and the peoples of Ethiopia reinscribes outdated cultural and sociopolitical norms of the 19th century as a contemporary reality.11 By the same token, we no longer need to watch Carmen, Aida and Butterfly wail their arias clad in extravagant costumes that are more complex than their characterisation. The perpetuation of an Orientalist fantasy through creative direction, makeup, and set and costume design is not only damaging to an art form that is already perceived as exclusive, but reveals that the success of opera companies at large is derived from an institutional insistence upon performing exoticised nostalgia in the name of authenticity.

An underlying presumption of opera is that if traditional Orientalist spectacles are not upheld, companies will lose their customary audience due to a loss in ‘quality.’ The dubious implication of quality being tied to outdated modes of casting and creative direction is a knee-jerk response from those conservatives who are in service to the ‘old ways.’ Opera Australia’s current productions rely on caricatures and actively contribute to the ongoing stereotyping of people of colour and their cultures, rather than engaging music, theatre and art to connect deeply with contemporary and local audiences. Opera Australia has the opportunity to inspire, reflect and tell deeply engaging stories that would no doubt attract younger and newer audiences. Instead the company chooses to pander to the its own ego and increasingly ageing demographic. It seems that traditional opera remains one of the final bastions for large-scale racial and cultural appropriation.

The inbuilt mythology of opera as the height of classical music has allowed for the perpetuation of such institutionally lazy practices. Internationally, opera has garnered a reputation for its feeble relationship to reality and has regularly drawn headlines for its outdated love affair with ethnic exoticism.12 But to say that this is all opera has to offer is false. Rather, the fault lies in companies such as Opera Australia who have propagated this unsustainable presentation of a living art form that has far more to showcase than archival reworkings.

Act III.

In 2011, the Artistic Director of Opera Australia, Lyndon Terracini, delivered the 13th Annual Peggy Glanville-Hicks address. With a great deal of optimism and passion, he proclaimed:

“Brave programming is having the courage to program what critics will criticize you for, but will make a genuine connection to a real audience, who will become passionate supporters of the art form.”13

Since his announcement as Director in 2009, only three Australian Operas have been commissioned or produced for its mainstage; one by Brett Dean (2010), one by Kate Miller-Heidke (2014), and one by Elena Kats-Chernin and Justin Fleming (2019), out of the estimated total of 152 operas. His call for “brave programming” rings hollow when all but less than 2% of all the mainstage operas staged under his direction to date have come from the well-trodden past. Furthermore, Terracini’s desire to encourage a healthy culture of critique came to a hypocritical juncture when, in 2015, he made headlines for barring two music critics from Opera Australia’s media list.14 Diana Simmonds of Stage Noise and Harriet Cunningham of Sydney Morning Herald were barred by Terracini due to their public critique of his artistic direction and parochial, Verdi-heavy programming. The critics received similar emails from the Opera Australia’s media department, with the one to Simmonds stating that “in response to some of your recent writing about the company, Lyndon asked that you be removed from the media list.”15 Terracini’s response to critique unveils Opera Australia as a company that is indifferent with making genuine connections with contemporary audiences, too staid to change even in the face of widespread criticism. Insofar as Opera Australia’s integration of digital technology is a flimsy veneer for its supposed modernisation, was Terracini’s impassioned 2011 proclamation nothing more than an offhand gesture to disguise the true culture of the company?

Fast-forward to 2017 when Opera Australia’s CEO Rory Jeffes announced that Opera Australia was the world’s most profitable opera company, and that it is “the world’s only major opera company where ticket sales exceed half of turnover.”16 Opera Australia continues to receive a large amount of annual state and federal funding—a combined average sum of between $24 and $26 million which increased to the amount of $37 million in 2020.17 As Professor Jo Caust asks us to consider, “Does opera deserve its privileged status within arts funding?”18

While opera’s history as a ‘luxury’ art form may be read as a classist and exclusionary pastime, the nature of Opera Australia’s public funding renders it in service to the public. It is an assumed responsibility when an organisation is granted such a degree of public support that they serve the public and its local practitioners. To address this observation, the following excerpt is taken from Marketing Beyond Your Core Audience by Georgia Rivers, a publication featured by Opera Australia:

“The classical performing arts are expensive… But the classical performing arts are part of our cultural heritage, so they won’t die out. They will join the superficial market that maintains art galleries and museums… It’s fleeting, but it keeps historic collections afloat… Our goal is to make seeing an opera at the world’s most famous opera house the default for every visitor to Sydney, regardless of their interest in opera.”19

The average ticket cost to the opera is over $100AUD,20 whereas access to view the permanent collections of state galleries and museums is often free. Why not seek to imagine the experience of opera along similar lines of accessibility? What might be inferred from Opera Australia’s goal is that their current model is geared towards tourists rather than the public who fund their artistic operations. The company’s relative indifference in trying to foster an innovative and sustainable culture of classical music through engaging with local practitioners and audiences is representative of practices within the industry at large. Opera Australia is merely a symptom.

The argument that classical music exists to only re-perform the greatest hits of the Western canon over the last 400 years implies that anything out of the ‘expected’ such as music by women, by people of colour, or anything commissioned in the recent decades, does not fall into this mythologised category of ‘the greatest music.’ Ironically, what has been elevated to the status of ‘the greatest music’ was commissioned and performed during their historical periods in which new music was constantly created and celebrated. At some point in history, all of Bach, Beethoven, Verdi and Puccini was new music. Today, attempts to broaden the nature of representing certain productions, their creative direction and the variety of composers being commissioned in the classical music world are met with hesitation and cyclical arguments about contemporary music not being economically viable.21 Perhaps these staunch critics against contemporary music and hearing new voices should be reminded that one of the most revered works of the 20th century, Igor Stravinsky’s La Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring), caused a riot amongst the audience when it was premiered on the 29 of May 1913 at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris. In Ciaran Frame’s publication, The Living Music Report 2020,22 the following statistics are laid out pertaining to the programming culture of major Australian orchestra and classical music companies:

18% of works were written by living composers

10% of works were written by Australian composers

4% of works were written by female composers

1% of works were written by CALD Australian composers

1% of works were written by First Nations composers

Such figures would not be considered acceptable in any other industry, let alone one that subsists on public money, totalling $81.9 million for Australian orchestras and $37 million for Opera Australia in 2020, to exist.23

Act IV.

The archaic practices Opera Australia continues to champion does a grave disservice to living practitioners who desire a pathway out of the archive. It comes at the expense of musicians and technicians that are active in their pursuit of new modes of storytelling, and who willingly interrogate and challenge the artform’s problematic elements within their own practices.

Opera Australia’s Orientalist fantasies are dislocated visions of ‘authenticity’ that do not deserve its privileged, government funded support. Their diminutive presentation of opera does little to create a thriving and sustainable future for classical music at large. If the focus of Opera Australia was to create art in a healthy culture of critique and public forum, opera would live beyond its self-imposed categorisation as a “historic collection.”24 Like historical artefacts, perhaps Opera Australia deserves to be processed, tagged and placed into a box deep within the bowels of a quiet collector’s archive. Because any organisation that insists upon relying on the privilege of the dead, presented in the manner of the dead, deserves the trajectory it draws for itself.