There’d been a door sticking. A security warder on the overnight shift was making the rounds when, in one of the basement corridors, there was a door that just wouldn’t open.1 He concluded that something on the other side was blocking it and took a detour using the tiny, padded lift that goes up through the Prints and Drawings department instead. The tiny lift stuck and trembled, moved a bit, then stuck and trembled again. It took five or six minutes to move just the one floor. As the lift shook, his feeling of being obstructed intensified, until he shouted skyward at the ghosts, “Stop playing silly buggers!” When he stepped out of the lift and arrived at the other side of the door that had refused to open, it wasn’t locked. There was nothing blocking it. It opened with ease.

He said that there were lots of times when these kinds of things happened—when doors wouldn’t open, and for no discernible reason. He attributed this to the “spirits of the place.”

Since 2016, I’ve been collecting ghost stories from current and former British Museum staff, and can attest that on many occasions the British Museum’s passageways have been blocked or left open—doors positioned contrary to operating procedure, unnerving those tasked with maintaining order in the museum. Describing an episode involving the often uncooperative doors which enclose the Sutton Hoo Gallery, one warder marvelled, “When we reviewed the CCTV back, you can see me and my colleague walk through, and then these doors, you see them just go like that…”, unfolding their fingers and slowly spreading them apart, “[opening] up inwards for no reason whatsoever. You’d need a very, very big breeze to open them up like that.”

Another warder, recalling a separate incident that took place in the Sutton Hoo Gallery, rejected the possibility of wind blowing the doors open: “Someone tried to put it down [to] wind. Well, if it was wind, how is it that the other doors didn’t open up? Where would the breeze come from?” He shook his head, as if to restate his bewilderment, “ That door should never have been open.” The Sutton Hoo Gallery is thick with such trickery. According to yet another warder:

“Between galleries 42 and 41, the doors were notoriously old and warped and difficult to shut. We got the one door, but then it just wouldn’t quite meet the other, and so my colleague slammed it, and kept slamming it, and then all of a sudden, the door that was closed flung back open. He felt something push against his chest.” With this, the warder pantomimed his wrist thrusting forward, as if pushing his colleague’s sternum and launching him—“a big lad”—into the air. His supervisor watched helplessly as “He got knocked right back off his feet, and onto his backside. And then the doors slammed. Bang!”

Patsy Sorenti, a psychic medium and historian of the Anglo-Saxon period, later asserted that at least some of the disturbances in Gallery 42 were caused by the conversion of the adjacent Medieval Christian Relics Gallery into the Islamic Gallery, spawning a rebellion among its incorporeal keepers, against the living guardians of the museum.

“Whoever was looking after that, whoever was linked to those objects, maybe more than one person, has got the hump, because you swapped Christianity for Islam, and in the Medieval world, in those times, that was the devil. Because you represent the people who work here [you] are responsible. That’s why the doors closed on you, and that’s why your man was thrown. That’s what it is – you’ve replaced Christianity, you have replaced it with something that’s a devil to us. You displaced us for that.”

Sorenti implies that the ideology and worldview of the ghosts who ejected staff from Gallery 42 remains fixed in the paradigms of the Medieval world. Suspended in the prejudices of their time, these spirits are enlisted in a conflict catalysed by one collection displacing another, by their holy objects being put uncomfortably close to those of their enemies.

While curators at colonial museums are afforded the privilege of neglecting the energetic import of the collections that they work with, for the warders, cleaners, and overnight security staff this is not so easily done. As a member of the permanent nights once told me, “You get objects that hold energy, and [people] go with those objects.”2

While curators research, catalogue, and prepare artefacts for exhibition, it is the lower-waged workers who spend the majority of their working hours on the museum floor, closely observing both the displays and visitors. While the museum trustees sleep, insulated from the blowback resulting from their decisions, it is the security, visitor services, and cleaning staff being thrown from, and chased out of galleries on the night shift. Unsurprisingly, the once-airborne warder described above left his position at the museum soon after his encounter.

These occurrences inside the Sutton Hoo Gallery are part of a greater constellation of stories where British Museum workers have been subject to unseen presences whose auras are unmistakably threatening. For instance, alarms are sometimes triggered to lure staff in, only for the spirits to toy with them—to let them know who really holds power inside the museum. These spectral flexes occasionally prompt museum workers to quit or withhold labour.

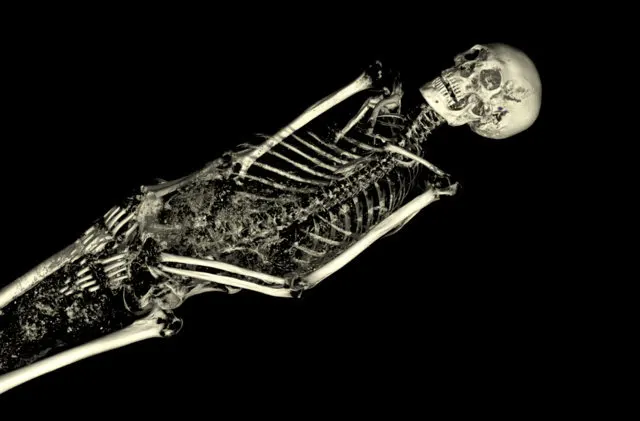

“There was a time when the cleaners refused to clean the cases in the mummy gallery because the mummies would move,” recalled Jim Peters, a long time Collections Manager. “So they refused. They genuinely believed that the mummies were moving, and refused to go in there. So, the museum had to do something about it, and get different people in.”

What to make of the cleaners’ collective refusal to enter the Upper Egyptian and Sudanese galleries? That a meeting of the broader British Museum staff was held to address this disquietude is testament to the enduring taboo of the exposed corpse, even in colonial and ethnological museums where their display has been naturalised by centuries of presenting bodies—both exhumed and unburied—so publicly. Mr. Peters seemed unconvinced by the museum’s account of the mummies’ alleged movement:

“The fact that the cleaners said they’d seen their wrappings rippling… The museum said, ‘Oh that was just the cleaners over-cleaning the cases! They’d caused a build up of static ‘cause the cases hadn’t been opened for awhile, so it built up the static charge in the air, and it meant things seemed to be moving, but they weren’t really.’ Everyone just went ‘Ahh thanks for explaining that, we can go back to work now…’ But you know, you’d have to be quite close, and they’d have to be quite light fabrics, and you’d have to be really aggressively over-cleaning… I never really bought that, but that was the resolution.”

Here, an ambiguity arises. Is it the aim of the spirits to obstruct the museum’s day-to-day operations, or is this manner of disruption simply the most effective way to declare their presence? If, by a process of deduction, informed by innumerable nights spent on patrol, the warder can find no “rational” cause for an entranceway being closed off or left agape, their mind may well turn towards the many powerful, restless, and unruly presences long held captive by the museum. The agency held in these so-called objects taunts the museum’s order, showing over and again a willingness to sabotage its smooth running, daring those who serve the museum’s interests to police what they can neither touch nor see.

Viewed through the lens of these hauntings, the museum appears as something akin to an object-prison: its hauntings like prison strikes, where cultural entities stage small revolts against their indefinite detention as stolen heritage, and their involuntary collusion in the public glorification of plunder and desecration of the sacred.

Since so many of earth’s sacred structures have been vandalised, dismantled and put on display in museums, perhaps the path to making them whole includes the slow, cumulative closing off of the museum’s arteries night after night—in a kind of ghostly insurgency.

Oral accounts are the substratum where the internal folklore of haunted museums tends to settle. Even the more senior members of staff shy away from filling out written reports of spirit activity, for fear of undermining their own credibility. “We try not to make fools of ourselves if we don’t have to!” one warder explained on behalf of his colleagues. Consequently, many such experiences go unvoiced. A previous director of the museum quashed attempts at collecting its ghost stories for publication, and so these stories are traded on patrol and at the pub, amongst those who know better than to speak dismissively of the “spirits of the place.”

“We was on another patrol, different part of the building. I can’t take you to these ones unfortunately, because it’s in the back of house, in an area they call the old horse stables. It’s primarily an old gallery that no one ever uses anymore, still objects down there, and a bit of a staff area. So I’ve gone up to turn the lights off. As I turn the lights off, it was like; you know when you get like a tingling sensation, like someone’s right behind you? It wasn’t dark at the time. The lights were still on, but it felt like someone…”

Her voice scattered as she sought to convey the feeling of being violated in a makeshift storage space.

“The only way I could perceive it was, someone had put their hand in, and grabbed my spine and sent the biggest chill up my spine… I kind of ignored it, and said to my colleague, ‘that was weird, you can unlock that in the morning. I refuse to go back there.’ He’s a Welshman, he was like, ‘Don’t worry about it, it’s fine, it’s fine…’ He went back in the morning to unlock it, and I followed him. When we got back to the same area again, I got the same chills but he actually had jelly legs as well, for no reason whatsoever… It completely put me off that whole area… It was that feeling of, ‘I’ll get up your back. I want you out my area’, and for him to say that he felt his legs go like jelly […] it even freaked him out, and we just went out of there as quick as you could say ‘boo.’ We were gone. We were gone.”

At the height of the British Empire, beset by rebellions and revolts, the British considered themselves masters of counterinsurgency, but such tactics are toothless against combative spirits. Conflicts that are presented as cooled, hardened and relegated to history books, reawaken nightly in museum corridors and storerooms, in ongoing battles of attrition: if a ghost causes a museum employee to acknowledge their presence, or hastens the worker’s exit from the institution, these may be seen as victories. It may be that their grievances have been felt, if not entirely understood. Or it may well be that divestment from the institution of the museum is precisely the sort of outcome the spirits desire.

Though they may appear anecdotal, dwelling as they do at the precipice of the unspoken, such small victories are many. When I asked one warder if he had the contact information of a woman he was on patrol with years ago, when a disembodied voice spoke to them on the North stairs just after midnight outside of the China and South Asia Gallery, he admitted he wasn’t sure how to get in touch.

“She’s left here a number of years ago now. She was very uneasy. She always felt something in this museum.”