In 1921, Amos A. Fries, Brigadier-General and United States Military Chief of the Chemical Warfare Service (CWS) published a military manual documenting the use of lethal gasses during wartime. This manual contained everything known about the use of these gasses by the US and other combatants during the First World War—including Britain, France, and Germany—as well as strategies that armies could implement to protect soldiers from them. Fries dedicated much of the 440-page manual to defending their prior use, advocating strongly for the continued deployment of chemicals and gasses in future wars, and arguing that it is the right of the “highly civilized…most scientific and most ingenious people” to use the strongest weapons possible against “savages.”1

A dedicated “chemical salesman,” war hawk, and anti-communist,2 Fries cut his teeth serving under then-Captain John J. Pershing during the American war against the Moros, the Muslim population indigenous to the southern Philippines. It was Pershing who oversaw the annihilation of the Moros, quashing their 11 year rebellion against the United States to bring the entire Philippines under colonial rule. Fries, who was present during the beginning stages of the United States’ counterinsurgency against the Moros, saw the use of chemical weapons as continuous with colonial warfare, arguing in his manual that if one were obliged to abandon chemical weapons in order to “fight fair,” then “American troops, when fighting the Moros in the Philippine Islands, would have had to wear the breechclout [loincloth] and use only swords and spears.”3

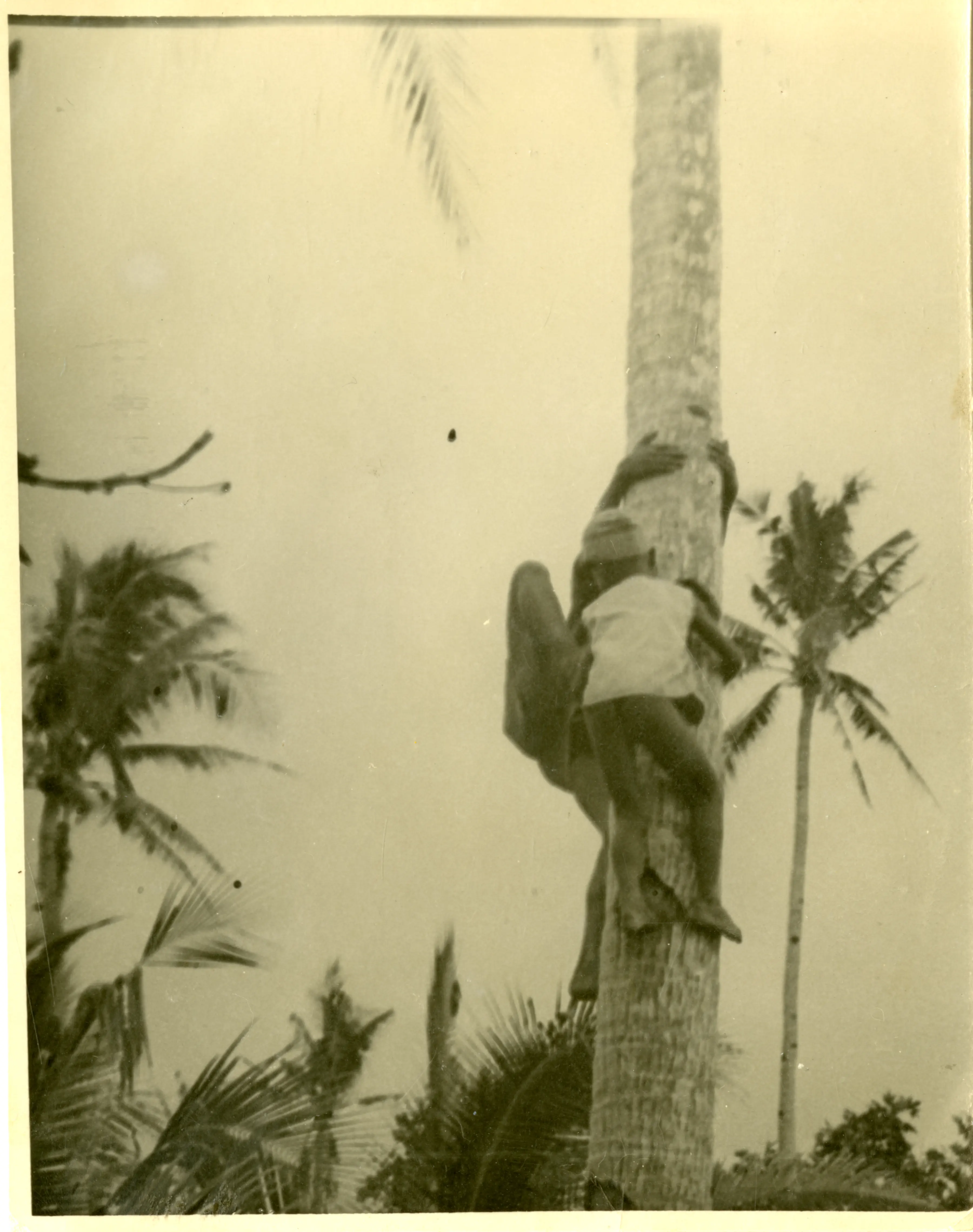

Chemical warfare accelerated in the years following 1915, when the Germans first used chlorine gas against the British and French to break a trench impasse. Consequently, the demand for protective gear was high. Coconut shells were known to produce the highest quality and most adsorbent charcoal for use in gas masks, and it is likely that in 1917, during World War I, Fries, remembering his time on the colonial frontier against the Moros, recalled the vast coconut production capabilities of the Philippines.4 Now known as the Chief of the Chemical Service in Europe (and appointed by General Pershing, no less), Fries seemed to have a pathway to meet the increased demand for protective gear in the age of chemical warfare. Demand for coconut charcoal reached its peak in 1918, several months before the Armistice, with 400 tons of shells being converted to coal each day, a scale of production that the United States could neither meet domestically nor through importation from Central America, the West Indies, and the Caribbean.5 Thus, Fries ordered a coal production plant to be created in the Philippines. This colonial territory, secured only four years prior, was not just vital for harvesting coconut shells but—in an early recognition of the efficiency of offshoring—the occupiers realized it is more enterprising to ship 10 tons of coal to the world than 10 tons of coconut shells.

This brief sketch of Fries’ military exploits as a colonial crusader and chemical warfare czar highlights the interstices of imperial conquest, resource extraction, and the destructive impacts of offshoring production. In turn, Fries’ story demonstrates how the contemporary global logistics regime reflects a distinctly colonial, capitalist, ecological dynamic.

Yet, something about our current capitalist geographies keeps us from seeing these networks “as they are.” In this case, the logistical infrastructure of late capitalism is specialized in obscuring the violent relations that structure global relations of production, circulation, and consumption. Laleh Khalili notes how militarized logistics have reshaped the Arabian Peninsula; a city’s docks and ports are no longer located along central rivers as they were until the twentieth century, but now shunted off to enclosed, securitized and deserted wastelands, out of sight. She writes: “The strange conjunctures of capitalism and trade and migrant labor and geopolitics and oil and dirt and filth and violence that make the sector are no less fascinating because they are made so invisible.”6

This making invisible is accomplished through the removal from pedestrian city centers but also, in large part, through sheer scale. There are two levels to this visual regime: it cushions our awareness of the mass devastation and dynamics of violence that underwrite our cheap and easy access to commodities from around the world. Making ourselves aware of our position in the global circuit of production is what Bruce Robbins calls “commodity recognition.”7 He argues that this requires paying “ethical attention” to the place of everyday commodities as “bearers of… the recognition that the objects we consume display the labor of others, much of it coming from distant places, and that in a sense we are beneficiaries of that labor belongs to capitalism’s basic sales pitch.” The observation that capital obscures the violences that sustains the production of value as well as our own implication and subjection within this dynamic is exacerbated by industrial globalization. As Edward Said famously elaborated in Culture and Imperialism (1993), the enslaved Caribbean labor on British-owned sugar plantations that sustained the manors of those in Jane Austen’s Britain were hidden in plain sight.

Part of our anti-colonial politics, then, must center the visual; in the sense of seeing what has been obscured. Or, by extension, in the sense of becoming “aware” of these dynamics in the first place. Many activist groups already incorporate this act of piercing the veil, so to speak. However, “making things visible” cannot be the end of our politics. Many see, quite clearly, the violence that subtends the comfortable consumption enjoyed in the Global North and, not even ignoring it, choose to promote it. In short, there is a whole terrain of struggle that opens up after we make things visible.

In spatial terms, “the logistical” is pervasive as a particular form of social mediation under late capitalism. As Søren Mau notes, our “individual metabolism is mediated by a complex system of infrastructures, data, machines, financial flows, and planetary supply chains.” The system is so vast that it can only be perceived in pieces; the apprehension of the forces that shape our lives has become ever more fragmentary and hidden from view. If infrastructure and logistics make these violent processes invisible, then a politics may emerge from, in Roland Barthes’ words, the point at which “a ubiquity [is] made visible.” While Barthes was referring to the miracle of plastic and its seemingly infinite transformations at the dawn of the 1960s Plastic Fantastic age, we can see how the infinite variation and endless points of connection that drive the dream of industrialized capitalist globalization fits the same mold. While hailed as being “revolutionary”—defined as having made life a bit easier for those in the so-called Global North—both globalization and industrialized capitalism have also been scourges of modern life, on a planetary scale, within a century of their appearance. As our climate crisis accelerates, its ongoing, day-to-day invisibility is a key point of intervention for those wishing to avert ecological collapse.

This is the underside of the neoliberal fantasy of “globalization.” Scholar Lisa Lowe notes that “globalization cannot be represented iconically or totalized through a single developmental narrative; it is unevenly grasped, and its representations are necessarily partial, built on the absence of an apprehensible whole.”8 While the supply chains and logistical infrastructure that shape our lives—such as the petroleum mega ports of the Arabian Peninsula—are hardly visible, if not incomprehensible, the everyday objects that arrive before us contain within them traces of this production and circulation. In short, looking toward smaller units of globalization, or what Lowe calls “metaphors,” can help us to decode or analyze the necessarily inapprehensible forces that buffet our lives.

Returning to Fries and the United States’ voracious imperial demand for charcoal, we can trace the routes of the coconut to understand how colonized territories bear the brunt of both colonial extraction and circulation. The United States government in 1918 began a patriotic campaign to gather peach pits to be converted into charcoal for gas masks. Like other home-front campaigns such as war bonds, food rationing, victory gardens and working in war-industry factories, the government mobilized civilians to make up for the industrial shortfall. Barrels were set up on street corners for civilians to drop their pits (including olives, apricots, plums, and cherries). This campaign created a cultural industry that spanned Scout rhymes to “Gas Mask Days,” and even cash rewards to encourage pit collection.

The cultural element of nationalism is important. What we see here is the divide between what results from a practice of commodity recognition, one that shows how “emotions shape the ‘surfaces’ of individual and collective bodies.”9 In numerous photographs documenting the peach pit effort, we see civilians having fun as they pitch in for “the boys.” Here, we can see how “recognition” operates on an emotional register: It can have the “positive” (that is, creative) effect of shoring up the patriotic national body through targeting consumer awareness, that the food they eat could impact the outcome of the war. In other words, it elucidates for the American civilian their position and stakes within the total circuit of production.

Conversely, little was—or is—known in the American popular imagination about the extraction of coconut resources from the colonial periphery. During Fries’ era, this was a process that remained a talking point of military-industrial circles, never crossing over into public discussion. This is illustrative of the central dynamic of colonialism’s visual regime: the mass extraction and funneling of resources from the Third World is hidden by those in the imperial core. The sheer fact that peach pits produced inferior coal (and given, also, that at least 200 pits were needed to produce enough coal for one gas mask canister), the domestic drive likely did very little for industrial production and more for the production of domestic patriotism. That the domestic drive for peach pits did more for those at home than those on the battlefield is especially evident when one compares its scale to what was extracted from the Philippines.

To put a finer point on this, the lower scale and inferior quality of domestic peach pit charcoal production illustrates how production in the metropole is largely useless on a material level and, in this case, was simply useful on an affective level to bolster waning spirits in the fourth year of a brutal war. Like the familiar economic protectionist mantra of “Buy American,” this nativist pretense relies on production and extraction in the colonies, which must necessarily remain both hidden and material: The consumer in the imperial core must never be made to think about the affective world of the colonized worker. The colony, its land and people, exist simply to produce for others. This visual regime exists everywhere today under neocolonial auspices, from the cobalt mines of the Democratic Republic of Congo to phone assembly plants in China, and is what Robbins targets with his demand for “ethical attention” to the commodities that actuate our lives.

This moment of massive demand for external resources is the flipside of the coin that David Harvey calls capitalism’s “spatial fix,” the constant solving of crises of overproduction through the export of capital to new markets abroad. Fries’ coconut fix is a fundamental example of the colonial-ecological dynamic that expands time, saves space, redistributes labor, and preserves the environment of the metropole through offshoring production time, land use, and the environmental costs of coal production to the Philippines. This colonial ecological relation is not confined to American imperialist ventures: Marxist geographer Alf Hornborg has described how cotton production in Industrial England used “strategies of conversion” to appropriate cheap land and labor elsewhere in the empire during the production cycle to enhance local accumulation. This is the material basis of global capitalism, in which the local saving of time and labor was exchanged at the expense of time, labor, and land abroad, a specific constellation of asymmetric resource flows and power relations.10

The thousands of tons of coconut charcoal needed to defend against German gas attacks, compounded with the environmental costs offshored from American soil were disastrous for the Philippines. This only worsened as coal production became more efficient through the invention of the Dressler Tunnel Kiln, an innovative piece of machinery in the ceramics industry that could apply heat at a consistent rate. It was appropriated into military use as its heat mechanism was found to be crucial in producing high quality coal with maximum adsorptive capability. Although the kiln could be operated using natural gas or conventional oil, it was coke, a carbon-rich residue of coal production, that won the day because it was, in essence, fueling its own creation. Because of its high carbon content—along with other harmful chemicals such as sulfur—coke combustion was highly destructive to the surrounding environment, killing surrounding vegetation and filling the air with silt, heavy metals, toxic particulates, and “fugitive dust” that could penetrate human airways. Fries noted in his manual that by the end of the war, they were processing 400 tons of coconut coal a day. At scale, this would mean tons of particulate matter being released into the Philippine atmosphere on a daily basis. For every worker in the Philippines exposed to the coal combustion exhaust, another in the US was spared.

The wages of our consumption today take place under the same lethal, though invisibilized, calculus: Not just through the expensive silicon-products that pervade our lives but through our clothes made for pennies in Bangladesh sweatshops and the frozen shrimp we buy caught by enslaved Thai fishers. Third World workers trade their lives—through labor, through the destruction of their local ecologies—for the meager wages that form the bedrock of our “affordable” lives.

These colonial dynamics of offshoring ecological and human destruction have not been restricted to the past or curbed through toothless accords. They have, in fact, stretched far into our present and, if our current trajectory holds, our future. So too have the reasons and justifications for offshoring: Fries ends the manual by advocating for increased chemical use with the chapter titled “Peacetime uses of gas,” which laid the groundwork for more recent explosions of so-called “less-lethal” crowd control munitions such as “Agent CS” (tear gas), “Agent OC” (pepper spray), and other irritant gases, aerosols, and oils.11 In this final chapter, he extols the virtues of gas used against domestic civilian populations: “No jail breaking, no lynching, no rioting can succeed where these grenades are available.”

Fries’ conviction and ardor for using lethal gasses, expressed in the most ruthless and messianic manner, reflects the “civilizing” or, more accurately, genocidal ideologies of the West. He argues that the lethality of chemical warfare would be the ultimate deterrent of the “most scientific nations” against those less developed who, he claims, are those most likely to wage war. This delineation between those deserving and undeserving of annihilation, the division between the civilized and the savage continues to shape our world. Robbins’ “commodity awareness” remains a relevant way to “hack” into the logistical regime and network of colonial extractive relations of our present, including the aftershocks of Fries’ enthusiasm for military production seeded into civilian life, and the colonial capital means of securing its production. Indeed, today, the Philippines still produces coconuts for gas mask production—but now they are being sent to China.

The violence that the capitalist logistical regime has facilitated pervades our world. Tear gas, which Fries promoted, breathlessly, as a supposedly humane munition to use against domestic and foreign populations, has also seen an ever widening production, sale, and use since the global uprisings of 2019 and 2020. This violence is a ubiquity, drawing from Barthes again, that we must make visible. Fortunately, there has been an organic movement amongst scholars and activists groups alike, to map out the routes our commodities travel, and to make visible these logistical tracks in the world of political action.

Dissenters, a QTBIPOC youth-focused anti-war group has focused on highlighting and disrupting the transnational operations of US weapon’s manufacturers like Raytheon and Boeing in the ongoing genocide of Palestinians in Gaza. Some labor unions representing dockworkers and stevedores in Greece and Italy have recognized and refused their role in moving weaponry and materiel towards the frontlines in Gaza. Autonomous organizations like the Chinese diaspora-focused 巴勒斯坦团结行动网络 (Palestine Solidarity Action Network) have exposed various Chinese firms’ complicity with apartheid, calling for state-owned enterprises like Hikvision—which supplies surveillance cameras with facial-recognition technology to “Israeli” checkpoints—to divest from the Zionist regime. Actionists across the world have targeted branches of “Israeli” firms who actively test and develop technology to surveil and target Palestinians, such as Elbit Systems. These activists focus our sights on the objects and smaller units of globalization that make the ubiquity of logistical and ecological violence visible; the first step in a counter-logistical politics of the future.